Nearing the end of 2018, we’ll be bombarded by the annual parade of “top ten” lists counting down everything from the year’s news events to songs and online fads. For those of us interested in understanding and preserving the events of the Civil War and Antietam’s Cornfield, here’s our own such list – the Cornfield casualty top ten.

By David A. Welker

The Battle of Antietam, America’s bloodiest single day, immediately claimed 3,654 lives and generated an additional 8,772 wounded and missing casualties on both sides, many of whom should properly be moved to the “killed” category. Sliced another way, the Union suffered 12,410 casualties, while the South bore 10,318 such losses – bringing the total butcher’s bill for 17 September 1862 to a staggering 22,728 losses.

Nowhere at Antietam was the human cost of this fight more evident than in David Miller’s Cornfield. Casualties there alone amounted to 8,850 (4,350 for the Union, with Confederate losses numbering 4,200) and when the integrally-related fighting in Miller’s West Woods property is included, casualties of the morning’s fighting reach 12,600 of the battle’s 22,728 total – over half.

Such terrible losses are almost incomprehensible and to make sense of it one’s mind often focuses on the numbers alone, sublimating the fact that each digit represents the life of a man who fell that day. At the same time, looking only at a single soldier’s death experience risks making the event too personal and so impossible to understand the sheer scale of the human loss. To comprehend both the personal suffering and the sheer scale of America’s loss on 17 September, it can be helpful to focus on the organizations to which these men belonged – the regiments, North and South, which formed the new military “families” in which these soldiers lived up to the very moment of their deaths. [1]

Some of these regiments are famous, storied units, while others have gained little notoriety for all their suffering. And as in the wider battle, most of the units that paid the greatest price at Antietam fought in the Cornfield and its related action in the West Woods, all claiming the “honor” of having suffered over 50 percent losses. So, let’s look deeper into the Cornfield’s “Casualty Top Ten”. First up is: [2]

Number 10 – the 4th Texas

The 4th Texas’ battle flag

Formed on 30 September 1861 from independent companies Texas sent to the seat of war in Richmond, the 4th got off to a rough start by mutinying, driving its harsh, West Point-trained Colonel Robert T. P. Allen from camp, to be replaced by Colonel John Bell Hood. Joining the newly-formed Texas Brigade on 1 October, the 4th was gratified to see its own commander Hood assigned brigade command on 3 March 1862. Numbering 470 men, the regiment’s first combat came at Eltham’s Landing before suffering more significant casualties at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill on the Peninsula, losing its commander and some 85 men. At Second Manassas the 4th Texas joined Longstreet’s massive flanking attack on 30 August, suffering 31 casualties but capturing a Union battery for the cost, and at South Mountain on 14 September the 4th lost eight men defending Fox’s Gap. Having seen considerable action already, the 4th Texas marched into Antietam as a battle-tested, veteran regiment.

Privates Emzy and G.M. Taylor, 4th Texas

Entering Miller’s soon-to-be-famous Cornfield on 16 September, the 4th was among the first Confederate units to encounter Hooker’s advancing Union I Corps troops late that evening. Deployed as skirmishers in front of Colonel William T. Wofford’s Brigade, the 4th Texas traded fire with Truman Seymour’s Federal brigade as it pushed into the East Woods. Joined by the 5th Texas, they halted the Yankees before falling back to rest behind the Dunker Church. At 7:00 a.m. on 17 September, the 4th Texas and Hood’s Division was called into battle, the men angrily abandoning their half-cooked breakfasts. Sweeping across the Hagerstown Pike, the 4th and Wofford’s Brigade wheeled left into the Cornfield and headed north toward the advancing Federals. Barely had Wofford’s Brigade reached the Cornfield’s center when Union fire from the western side of the Pike—Stewart’s section of the 4th US Battery B and its 80th New York infantry support—stopped the attack in its tracks. To deal with the threat, General Hood ordered the 4th left to the Hagerstown Pike, where one 4th Texan recalled “[R]ight here, when we reached the top of the hill, was the hottest place I ever saw on this earth or want to see hereafter. There were shot, shells, and Minie balls sweeping the face of the earth; legs, arms, and other parts of human bodies were flying in the air like straw in a whirlwind. The dogs of war were loose, and “havoc” was their cry.” So effective was the 4th Texas’ fire that it halted Bachman’s advancing Union brigade, whose commander assumed he was facing an entire Southern brigade. When finally driven back with the rest of Hood’s Division by Meade’s advancing, fresh Union I Corps division the 4th Texas discovered its casualties were fearful—the greatest the regiment suffered during the war—losing 57 killed, 130 wounded, and 23 missing – a casualty rate of 53.5 percent. [3]

Number 9 – the 10th Georgia

Lafayette McLaws

Like the 4th Texas, Georgia’s 10th Infantry formed in Richmond, in June 1861, and its first field commander, Colonel Lafayette McLaws, quickly rose to prominence, assuming brigade command on 25 September, replaced by Colonel Alfred Cumming. Assigned to McLaws’ Brigade in Magruder’s Division, the 10th experienced its first combat in April, defending Yorktown from McClellan’s advancing Union host. Brigadier General Paul Semmes became their brigade chief when General McLaws rose to division command, and under Semmes’ leadership the 10th Georgia gained ever-greater combat experience at Mechanicsville, Malvern Hill, and Savage’s Station, suffering there 59 casualties. Guarding Richmond until early September, the 10th rejoined Lee’s army as it advanced into Maryland. Fighting at South Mountain on 14 September brought 60 casualties and a series of command changes, leaving the 10th to be led by Company H’s grandly-named Captain Philologus H. Loud. Consisting now of only 184 officers and men, the 10th Georgia marched through Pleasant Valley to Harpers Ferry, before heading north to join Lee’s gathering force at Sharpsburg at dawn on the 17th. [4]

Brigadier General Raphael Semmes

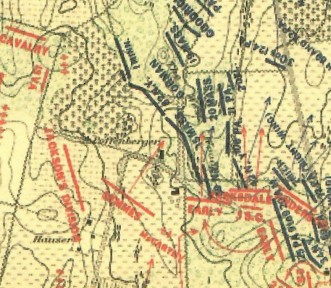

Resting briefly in the fields west of town, the 10th Georgia and McLaws’ Division hastily moved into battle around 9:00 a.m. Reaching the western edge of the West Woods—held then by Sedgwick’s Federal division of Sumner’s II Corps—McLaws immediately sent his men into the fight. Unleashing a two-pronged eastward-heading assault on Sumner’s vulnerable flanks, McLaws’ righthand attack was led by Barksdale’s Brigade near the Dunker Church while Semmes’ Brigade led the left prong’s assault. Deploying the 32nd Virginia on his right—with the 10th Georgia, 15th Virginia, and 53rd Georgia to the left—Semmes’ Brigade swept northward to the right of the Hauser farm, catching their first Yankee fire of the day from Gorman’s 15th Massachusetts and 82nd New York. Semmes briefly had his brigade return this “galling fire,” but not yet being on the Yankees’ flank, onward it went, men climbing the fence east of the Hauser house before pressing into a stubble field where they fell with each step. In response, Semmes ordered a dead run until reaching the Alfred Poffenberger farm, there reforming behind shelter of the barn and a series of low rock ledges. Now the 10th opened fire on the Yankees at close range, tearing apart Gorman’s Brigade’s unprotected right flank. Unable to return fire and facing threats in front and right, Gorman’s Yankees broke – and in their wake Semmes’ men pushed forward. Despite driving the enemy like sheep, Semmes’ Brigade lacked a plan and with little command oversight, Semmes’ assault quickly collapsed. Semmes pushed the 10th Georgia forward on the left to shore up the position, but it was too late. Facing a massive Union artillery force in front and flank, Semmes’ casualties mounted, quickly forcing a hasty retreat. The 10th Georgia—exposed on the left, facing the worst of the Union artillery fire—had taken tremendous casualties in those few minutes. This and the rush across the Hauser’s stubble field cost the regiment 84 of it 148 men, causing 56.7 percent casualties. [5]

Number Eight – the 15th Massachusetts

The 15th Massachusetts’ National Flag

Mustered into Federal service on 12 July 1861, the 15th Massachusetts arrived at the seat of war in Washington on 25 August. The 15th’s first combat was devastating, nearly as costly as its Antietam toll; the 21 October Union disaster at the Battle of Balls Bluff cost the regiment 324 casualties, over half its 600 green men. Assigned in April 1862 to the Army of the Potomac’s II Corps, Second Division, First Brigade—where the 15th Massachusetts remained until ending its service in 1864—the regiment participated in the Peninsula Campaign, suffering relatively minor loses at Seven Pines, Savage’s Station, and Glendale. Joined by the attached 1st Company of Massachusetts Sharpshooters, the 15th returned to Washington in mid-August, helping cover the Union retreat after Second Bull Run. Marching north with General Sumner’s reunited II Corps—its division under General Sedgwick and Brigadier General Willis A. Gorman commanding the brigade—the 15th crossed Antietam Creek early on 17 September, headed toward the growing sound of battle in the Cornfield. [6]

Passing through the Union-held East Woods, the 15th Massachusetts and Sedgwick’s Division moved into the Cornfield, where General Sumner ordered them into a “column of brigades – Howard’s the rear, Dana’s the center, with the 15th’s Gorman’s Brigade in the lead. Gorman’s right was held by the 1st Minnesota, with the 82nd New York, 15th Massachusetts and 34th New York to the left. Pushing through the shattered Cornfield, across the Hagerstown Pike, and into the West Woods nearly unopposed, Gorman’s men continued to the Woods’ western edge – for the first time this day reaching the main Confederate line. The 15th Massachusetts, however, suddenly found itself holding the brigade’s exposed left flank, the 34th New York having inexplicably disappeared during the advance. Instantly under fire from Confederate troops on the opposite ridgeline—Pelham’s six-gun battery, their 13th Virginia infantry support, and Grigsby’s Stonewall Brigade—things only grew worse when McLaws’ Confederate reinforcements swept onto Gorman’s exposed left and then on their right flank, too. Facing threats from front and flanks, Gorman’s Brigade found itself trapped in place by Dana’s Brigade, just arrived immediately in its rear. Worse, a terrified portion of the 59th New York—Number Five on our list—immediately in the 15th’s rear opened a panicked fire on the Bay Staters. Simply too much for Sedgwick’s men, both brigades almost at once dissolved, racing for safety. Although some 15th Massachusetts men joined the 1st Minnesota in rallying behind a low stone fence, they were soon driven back again. While survivors raced to the North and East Woods, the regiment left many men behind, including Sergeant Jonathan Stowe who wrote “Misery acute, painful misery. How I suffered last night… Many died in calling for help…Sgt. Johnson who lies on the other side of the log is calling for water… Water very short. We suffer much.” Sergeant Stowe joined the 334 men the 15th Massachusetts lost—nearly double the combined losses of the 4th Texas and 10th Georgia—resulting in 56.7 percent losses. [7]

Passing through the Union-held East Woods, the 15th Massachusetts and Sedgwick’s Division moved into the Cornfield, where General Sumner ordered them into a “column of brigades – Howard’s the rear, Dana’s the center, with the 15th’s Gorman’s Brigade in the lead. Gorman’s right was held by the 1st Minnesota, with the 82nd New York, 15th Massachusetts and 34th New York to the left. Pushing through the shattered Cornfield, across the Hagerstown Pike, and into the West Woods nearly unopposed, Gorman’s men continued to the Woods’ western edge – for the first time this day reaching the main Confederate line. The 15th Massachusetts, however, suddenly found itself holding the brigade’s exposed left flank, the 34th New York having inexplicably disappeared during the advance. Instantly under fire from Confederate troops on the opposite ridgeline—Pelham’s six-gun battery, their 13th Virginia infantry support, and Grigsby’s Stonewall Brigade—things only grew worse when McLaws’ Confederate reinforcements swept onto Gorman’s exposed left and then on their right flank, too. Facing threats from front and flanks, Gorman’s Brigade found itself trapped in place by Dana’s Brigade, just arrived immediately in its rear. Worse, a terrified portion of the 59th New York—Number Five on our list—immediately in the 15th’s rear opened a panicked fire on the Bay Staters. Simply too much for Sedgwick’s men, both brigades almost at once dissolved, racing for safety. Although some 15th Massachusetts men joined the 1st Minnesota in rallying behind a low stone fence, they were soon driven back again. While survivors raced to the North and East Woods, the regiment left many men behind, including Sergeant Jonathan Stowe who wrote “Misery acute, painful misery. How I suffered last night… Many died in calling for help…Sgt. Johnson who lies on the other side of the log is calling for water… Water very short. We suffer much.” Sergeant Stowe joined the 334 men the 15th Massachusetts lost—nearly double the combined losses of the 4th Texas and 10th Georgia—resulting in 56.7 percent losses. [7]

Number Seven – the 18th Georgia

The 18th Georgia’s Battle Flag

Organized by William T. Wofford in April 1861, the 18th Georgia arrived in Virginia after the First Battle of Manassas and found itself guarding that battle’s prisoners, before becoming the first non-Texan regiment assigned to Hood’s Texas Brigade. With the Texans on the Peninsula, the 18th Georgia experienced its first fighting at Eltham’s Landing, followed by Gaines’ Mill—suffering 143 casualties, more than at Antietam—and Seven Pines. At the Second Battle of Manassas, the regiment captured the 10th and 24th New York’s colors, but suffered another 124 casualties in the process. Marching into Maryland on 3 September, the 18th fought at South Mountain before retreating to join Lee’s stand at Sharpsburg. After skirmishing with Seymour’s advancing Federals in Miller’s Cornfield late on 16 September, the 18th and the Texas Brigade—now commanded by the regiment’s own Colonel Wofford—retired to rest near the Dunker Church. [8]

An 18th Georgia private

Joining Hood’s Division, at 7:00 that morning the 18th Georgia scarfed down what little breakfast had been cooked and marched into the Cornfield to halt Hooker’s opening assault. Forming the left of Hood’s line, immediately right of the Hampton Legion, the 18th advanced deep into the Cornfield until stalled by galling Union fire from across the Hagerstown Pike. Facing Stewart’s section of the 4th US artillery and its infantry support, the 80th New York, the 18th Georgia’s Lieutenant Colonel Ruff and the Hampton Legion’s commander shifted their regiments’ fronts left, facing and returning fire on the Union guns. Enduring artillery canister and infantry fire at such close range tore huge gaps in the Georgians’ ranks, but the 18th men could do little more than endure until Colonel Wofford and General Hood sent reinforcements. Their fire was gradually thinning the Yankee guns’ crews, suggesting victory was near, but before help arrived Patrick’s fresh Union brigade appeared, signaling the beginning of the end for the Georgians. Nearly flanked on the right and being torn apart by fire, Wofford’s last hope disappeared when his intended support, the 1st Texas, “slipped the bridle” and marched away, leaving the Georgians on their own. Retreat was their only hope and even that came too late for many – the 18th Georgia left 101 of its 176 men on the field, resulting in 57.3 percent casualties. [9]

Number Six – the 15th Virginia

The 15th Virginia’s regimental colors

The 15th Virginia was formed on 17 May 1861 by Colonel Thomas P. August, comprised of men from the Richmond area counties of Henrico and Hanover. Assigned to General McLaws’ Brigade, the 15th Virginia experienced its first combat at one of the war’s earliest battles, the Battle of Big Bethel on 10 June 1861, before taking part in driving the Federals from the Virginia Peninsula at the Battles of Savages’ Station and Malvern Hill. The 15th had fought there as part of Semmes Brigade—along with the 10th Georgia, Number Nine on our list—since September 1861, when McLaws had risen to command their division. Marching north into Maryland on 3 September 1862, the 15th endured its next combat during the South Mountain battle, part of the small force defending Crampton’s Gap from Union VI Corps assaults. Rejoining McLaws’ Division in Pleasant Valley on 15 September, the regiment marched through Harpers Ferry until called to join Lee’s gathering force at Sharpsburg before dawn on 17 September. [10]

Arriving and resting in the fields west of town, at 9:00 a.m. the Virginians and McLaws’ Division started across country toward the sound of battle. Commanded now by Company C’s Captain Emmet Masalon Morrison, the regiment and Semmes’ Brigade had barely reached the West Woods’ western edge before finding themselves marching north toward Sedgwick’s surging Union division, then threatening to break the Confederate line. Encountering their first fire of the day—from Gorman’s Brigade—Semmes had his men briefly return fire, before ordering them at a run to the safety and security of a barn and some low stone ridges. This rush achieved its goal but the 15th nonetheless left several men behind in Alfred Poffenberger’s stubble field. Holding here briefly while General Semmes moved a flanking force around the Yankees’ right, the 15th suddenly lost its commander when Captain Morrison was wounded in the chest (Morrison recovered, but was an unwilling guest of Uncle Sam until April 1863). Now under command of Company A’s Captain Edward J. Willis, the 15th charged the weakened Union position and joined in driving Gorman’s Brigade and Sedgwick’s Division from the West Woods and back across the Hagerstown Pike, only to be driven back themselves into the West Woods’ safety by Yankee artillery. When the 15th Virginia finally rallied in the Confederate rear, it became apparent it had lost 75 of its 128 officers and men, resulting in 58.5 percent casualties. [11]

Arriving and resting in the fields west of town, at 9:00 a.m. the Virginians and McLaws’ Division started across country toward the sound of battle. Commanded now by Company C’s Captain Emmet Masalon Morrison, the regiment and Semmes’ Brigade had barely reached the West Woods’ western edge before finding themselves marching north toward Sedgwick’s surging Union division, then threatening to break the Confederate line. Encountering their first fire of the day—from Gorman’s Brigade—Semmes had his men briefly return fire, before ordering them at a run to the safety and security of a barn and some low stone ridges. This rush achieved its goal but the 15th nonetheless left several men behind in Alfred Poffenberger’s stubble field. Holding here briefly while General Semmes moved a flanking force around the Yankees’ right, the 15th suddenly lost its commander when Captain Morrison was wounded in the chest (Morrison recovered, but was an unwilling guest of Uncle Sam until April 1863). Now under command of Company A’s Captain Edward J. Willis, the 15th charged the weakened Union position and joined in driving Gorman’s Brigade and Sedgwick’s Division from the West Woods and back across the Hagerstown Pike, only to be driven back themselves into the West Woods’ safety by Yankee artillery. When the 15th Virginia finally rallied in the Confederate rear, it became apparent it had lost 75 of its 128 officers and men, resulting in 58.5 percent casualties. [11]

The 15th Virginia’s Dr. Alexander Harris and his wife (L); During the War (R)

Number Five – the 59th New York

Organized chiefly from throughout the New York City area by Colonel William L. Tidball, on 23 November 1861 the 59th New York left for Washington, eventually joining Wadsworth’s force guarding the Union capital. Despite several command changes, the regiment remained largely static until June 1862, when it joined the Army of the Potomac at Harrison’s Landing on the Virginia Peninsula, attached to the II Corps’ Second Division—commanded by John Sedgwick—and the Third Brigade, led by Brigadier General Napoleon J. T. Dana. By late August—still not having experienced combat, although present at Malvern Hill—the 59th was pulled from the Peninsula and shipped to Northern Virginia, there covering the retreat of Pope’s defeated Union Army of Virginia after the Second Battle of Manassas. Advancing into Maryland searching for Lee’s invading army, the 59th New York and its II Corps comrades reached Frederick on the 12th, remaining in reserve during the Battle of South Mountain. The 59th still hadn’t “seen the elephant,” but that was soon to change… [12]

Organized chiefly from throughout the New York City area by Colonel William L. Tidball, on 23 November 1861 the 59th New York left for Washington, eventually joining Wadsworth’s force guarding the Union capital. Despite several command changes, the regiment remained largely static until June 1862, when it joined the Army of the Potomac at Harrison’s Landing on the Virginia Peninsula, attached to the II Corps’ Second Division—commanded by John Sedgwick—and the Third Brigade, led by Brigadier General Napoleon J. T. Dana. By late August—still not having experienced combat, although present at Malvern Hill—the 59th was pulled from the Peninsula and shipped to Northern Virginia, there covering the retreat of Pope’s defeated Union Army of Virginia after the Second Battle of Manassas. Advancing into Maryland searching for Lee’s invading army, the 59th New York and its II Corps comrades reached Frederick on the 12th, remaining in reserve during the Battle of South Mountain. The 59th still hadn’t “seen the elephant,” but that was soon to change… [12]

Regimental flank marker

Crossing the Antietam midmorning with Sedgwick’s Division, the 59th and Dana’s Brigade pressed on toward the sound of battle, pausing briefly to form their battle line before passing through the East Woods and into the Cornfield. Dana’s men and the 59th comprised the second line of the “column of brigades” General Sumner had ordered for moving into the fight, between Gorman’s and Howard’s commands. Following behind Gorman’s Brigade, General Dana suddenly halted his command, ordering the men all to lay down. Why this was ordered remains a mystery, but barely had they hit the shattered cornstalks before the men were back on their feet and advancing once more. Reaching Gorman’s brigade’s position deep in the West Woods, the 59th instantly found it had marched into a swirling hell. Almost at once, Dana pulled away his left-most regiments—the 7th Michigan and 42nd New York—to counter an unexpected threat there, leaving the untried 59th New York holding the brigade’s left flank. And just as the 59th men realized they had this new role, McLaws’ flanking attack hit Sedgwick’s Division in its earnest. The fury of McLaws’ attack by Barksdale’s Brigade was so intense that both Generals Dana and Sedgwick were wounded amidst the fire pouring in on the unguarded left of Sedgwick’s three brigades. In reply, Gorman’s front-most brigade intensified its fire, while Howard’s brigade, the rear-most line, would shortly flee – until they did so, the largely green 59th New York and Dana’s two remaining regiments were trapped, able only to stand and take this death. Beginning to waver, some 59th men began firing through the 15th Massachusetts—Number Eight on our list—in their front at enemy targets as they appeared; this “friendly fire” felled several of the Bay Staters until General Sumner stopped it with a stream of invective. Mercifully, Sumner also ordered the 59th and Dana’s survivors away northward, toward Nicodemus Hill. The 59th New York’s first battle would prove to be its costliest of the war – losing 224 of the 381 men it had carried into the woods, resulting in 58.7 percent casualties. [13]

The 59th New York’s Antietam monument

Number Four – The 3rd Wisconsin

The 3rd Wisconsin’s regimental flag

The 3rd Wisconsin Infantry formed at Fond du Lac on 19 June 1861 under West Point graduates Colonel Charles S. Hamilton (1843) and Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Ruger (1854), although Ruger soon assumed sole command. By mid-July the regiment arrived in Washington, moving frequently between the capital, Frederick, Maryland, and Harpers Ferry, Virginia during the remainder of 1861. The 3rd first experienced combat on 16 October when Companies A, C, and H skirmished with Turner Ashby’s Confederate cavalry on Bolivar Heights above Harpers Ferry, resulting in 11 casualties. Although 1862 brought more geographic and organizational ping-pong for the 3rd, it nonetheless remained attached to the same brigade. During March through May the regiment participated in several small actions throughout the Valley, including the battles of Kernstown and First Winchester, before joining Pope’s Union Army of Virginia in June for the Battle of Cedar Mountain. On 6 September the 3rd Wisconsin and General George H. Gordon’s Brigade was reassigned to the XII Corps’ Williams First Division, where it would remain throughout the war and begin the march north into Maryland in pursuit of Lee’s invading Confederate army. [14]

The 3rd crossed the Antietam late on 16 September and spent a drizzly, restless night on the Hoffman farm anticipating battle at dawn. They and Gordon’s Brigade waited while Hooker’s I Corps marched into battle, then watched as their own division mates in Crawford’s Brigade struggled to take the East Woods. Next, the 3rd and Gordon’s Brigade swept forward to deploy across the Cornfield’s northern edge, arriving just in time to drive back Ripley’s Brigade, the latest Confederate effort to retake the Cornfield. Rather than pursuing Ripley’s retreating command, however, the 3rd and Gordon’s men now remained immobile – and completely exposed to fire from S. D. Lee’s Confederate artillery firing from before the Dunker Church. This pause was dictated by General Hooker’s revised plan in which Greene’s Division would sweep like a barn door through the East Woods before joining Gordon’s and Crawford’s Brigades to advance the entire XII Corps in finally taking the Cornfield. Though critical for the success of Hooker’s plan, it had deadly consequences for the 3rd Wisconsin men. With the arrival of Greene’s men, the 3rd Wisconsin joined in advancing to the Hagerstown Pike, securing for the Union once and for all control of the bloody Cornfield. This achievement, however, came at great cost for the Wisconsin boys, who left 200 of their fellow soldiers scattered across the Cornfield, resulting in 58.8 percent casualties. [15]

Gordon’s Brigade in the Cornfield, the 3rd Wisconsin on the right

Number Three – The 27th North Carolina

Formed in New Bern during June 1861—first as the 9th and later the 17th Regiment, but ultimately designated the 27th North Carolina—it’s first action came on 14 March 1862 at the Battle of New Bern before taking part in fighting on the Virginia Peninsula. Marching north into Maryland, the 27th was now part of Manning’s Brigade, in Walker’s Division, assigned to Longstreet’s Wing of the Army of Northern Virginia. After destroying the Chesapeake and Ohio canal’s aqueduct—part of Lee’s plan to sever Union communications during his invasion—the 27th and Walker’s Division reentered Virginia to occupy Loudon Heights, joining in Jackson’s capture of Harpers Ferry. This accomplished, the regiment and Walker’s Division started for Sharpsburg early on 16 September and by evening was resting in reserve behind town. [16]

Colonel Cooke

As the battle raged, the regiment and Manning’s Brigade remained in reserve until around 9:00 a.m. when it was forwarded to the West Woods, joining with McLaws’ Division. The 27th and Manning’s Brigade reached the woods’ western edge just as Sumner’s Federals of Sedgwick’s Division were threatening to break through Lee and Jackson’s line there. As Walker’s Division continued toward the woods, the general detached Manning’s 27th North Carolina and 3rd Arkansas—placing the 27th’s Colonel John R. Cooke in command—to close a gap between the West Woods and Longstreet’s troops in the Sunken Road. Deploying on the northern edge of the Reel family’s cornfield, the two regiments immediately opened a covering fire for Cobb’s small brigade, forming behind it in the corn. Their fire so troubled Greene’s Federals, then holding an advanced position immediately south of the Dunker Church, that a gun from Lieutenant James D. McGill’s section of Knap’s Battery E, Pennsylvania Light Artillery was brought forward to deal with the 27th and 3rd Arkansas. Recognizing the threat, General Longstreet ordered Cooke to charge, along with Cobb’s Brigade. Attacking at once, the 27th North Carolina and 3rd Arkansas’ line slammed into Greene’s 3rd Maryland, turning the Federals’ left flank. At the same moment, an unintentionally jointly-timed attack by Ransom’s Brigade on Greene’s exposed right joined in forcing the Yankees to flee. Cooke ordered his two regiments forward into the gap; pushing swiftly over the Hagerstown Pike and south of the Cornfield, where they became increasingly disordered. Ordered to slow and reform, the 27th’s color bearer explained to Cooke “Colonel, I can’t let that Arkansas fellow get ahead of me.” The two stabilized regiments pressed on until slamming into Kimball’s Brigade from French’s Division, still recovering from its earlier attack on the Sunken Road. Facing west and using the terrain for cover, Kimball’s men halted both Cooke’s regiments and Cobb’s Brigade in their tracks, while Irwin’s Brigade of the VI Corps headed right for them from the direction of the Mumma farm buildings. In an exposed position, enduring artillery fire, and facing a soon-to-be-reinforced, largely concealed foe was too much for Cooke’s rattled regiments. Cooke’s Arkansans and the 27th North Carolina fled, the latter leaving behind 199 men, some 61.2 percent of their force. [17]

Number Two – The 12th Massachusetts

Col. Fletcher Webster

Fletcher Webster, famed US Senator Daniel Webster’s son, raised the 12th Massachusetts from across the Boston area in June 1861, becoming its first colonel. Departing for Washington on 23 July, the 12th performed guard duties in the Frederick, Maryland area until February 1862. Moving into Virginia to join the Army of the Potomac, the regiment experienced its first combat while on picket duty along the Rappahannock River on 18 April. Assigned to Brigadier General George Hartsuff’s Brigade—where the regiment would remain through Antietam—they soon became part of Banks’ III Corps of the Army of Virginia – where the 12th would truly “see the elephant” in earnest. Arriving late to the Battle of Cedar Mountain on 9 August, the regiment nonetheless suffered 11 casualties to late-day artillery fire. On 30 August at the Second Battle of Manassas the regiment experienced its first significant combat as part of Tower’s Brigade; standing on Chinn Ridge against Longstreet’s half of Lee’s army cost the 12th Massachusetts 138 casualties. Reassigned to the Army of the Potomac’s I Corps, the 12th joined the chase for Lee’s invading army on 6 September. Suffering no casualties during the contest for Turner’s Gap at the Battle of South Mountain, the 12th Massachusetts pressed on toward Antietam Creek on the 16th. [18]

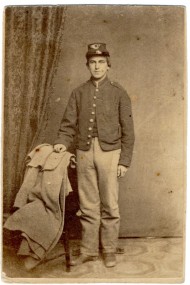

Pvt. John E. Gilman

Rising before dawn to the sound of shelling opening the battle, the 12th Massachusetts and Hartsuff’s Brigade found themselves in the first wave of Hooker’s opening Union attack that sought to break Lee’s line at the Dunker Church. Even before moving Hartsuff’s Brigade endured shelling and infantry fire that claimed General Hartsuff himself, shifting command to the 11th Pennsylvania’s Colonel Coulter; as ignorant of Hooker’s plan as his men, Coulter and his new command watched Duryee’s Brigade—with which they were meant to advance—sweep past them toward the Cornfield. Soon, though, Coulter led Hartsuff’s Brigade forward through the northern end of the East Woods and into the Miller’s grassy field, on a collision course with Lawton’s and Hays Confederates in the Cornfield. Once into the Cornfield and engaged with Lawton’s Confederates, Coulter shifted the 83rd New York and 13th Massachusetts to face almost directly west, aligned with the western edge of the East Woods to anchor his brigade’s position; however, this left the 11th Pennsylvania and the 12th Massachusetts in the open Cornfield to face Hays’ advancing brigade, moving to join Lawton. Worse, S.D. Lee’s artillery deployed near the Dunker Church continued ripping holes in their lines; so intense was this fire that it claimed the 12th Massachusetts’ commander, Major Burbank, and a single shell swept away the 12th’s entire color guard, dragging the colors to the ground. Amidst the tumult of this terrific fighting the Bay Staters ignored their fallen flag for some time, preferring instead to close-up gaps and continue firing. The 90th Pennsylvania’s arrival finally ended this nightmare but the 12th Massachusetts had paid a fearful price – leaving 224 of it 334 men on the field, the regiment had suffered 67 percent casualties. [19]

The 12th Massachusetts’ Antietam monument

Number One – The 1st Texas

First Texas men in winter camp

Nicknamed the “Ragged Old First,” the 1st Texas formed in Richmond, Virginia in August 1861 and by October had joined with the 4th and 5th Texas and 18th Georgia—Number Seven on our list—to form the Texas Brigade. On 7 May 1862 the 1st Texas and its brigade endured its first real combat at the Battle of Eltham’s Landing, later taking part in turning back McClellan’s army from Richmond at the battles of Seven Pines and Gaines’ Mill. Moving into northern Virginia, the 1st took part in the First Battle of Rappahannock Station on 22-25 August and at Second Manassas with the brigade—now commanded by Colonel William Wofford, who replaced Hood upon his move to lead the division—participated in Hood’s costly twilight clash with Hatch’s Federals at Groveton on the Warrenton Turnpike. Marching into Maryland on 3 September, the 1st Texas and Hood’s Division on 14 September blunted the Union IX Corps’ final effort to push through Fox’s Gap at South Mountain. Moving to the ridge north of Sharpsburg, the 1st and Hood’s men encountered Hooker’s advancing Yankees in Miller’s Cornfield as daylight waned on 16 September. Retiring behind the Dunker Church in the dark, the 1st Texas men grabbed some much-needed rest.

“Slipping the bridle”

The 1st and other Texas Brigade men were furious at being roused from breakfast to return to battle but nonetheless formed up and headed for the then-Union held Cornfield. Once deployed facing north, the 5th Texas held the Texas Brigade’s right flank, with the 4th and 1st Texas, 18th Georgia, and Hampton’s Legion respectively, to their left; to their right was division partner, Law’s Brigade. Starting at once northward, Hood’s Division almost instantly fractured as Hood sent Law’s command angling toward the East Woods while Wofford’s Texans continued due north toward the worn Federals of the Iron Brigade. Reaching nearly the Cornfield’s center, the brigade unexpectedly halted as the Hampton Legion and 18th Georgia responded to fire from the 4th US Artillery, Battery B and infantry across the Pike – leaving the brigade as static targets for Ransom’s 5th US Artillery, Battery C, just north of the cornfield. General Hood and Colonel Wofford both knew that only restarting the assault would end this suffering and both acted to break the logjam on the Texans’ left. Each pulled a regiment from the center, sending them left; Hood ordering the 4th Texas westward to the Hampton Legion’s left while Wofford directed the 1st Texas to the brigade’s right on the pike. With no coordination, the 1st started forward, driving away their most evident threat, Ransom’s artillerymen. Seeing the Yankees run only encourage the 1st men and on they drove, continuing past their intended post until they reached the northern end of the Cornfield. General Hood later observed that the 1st Texas had “slipped the bridle and got away from the command,” and in doing so they walked straight into the face of Meade’s Pennsylvania Reserves, who arose to pour a solid wall of fire into the advancing Texans; exposed and alone, they ran. Men fled in such confusion that they left behind their beloved Texas Lone Star regimental color, made by the daughter of Colonel Wigfall, their first commander, using pieces of her mother’s wedding dress. Worse, of the 226 men who’d marched into the Cornfield, 170 had been killed or wounded, giving the 1st Texas an appalling 82.3 percent casualties, the highest of any regiment on a single day, on either side, for the entire war. [20]

These regiments were more than just numbered organizations to the men comprising them, they often became the soldier’s temporary family which held his relations and friends from home, from both North and South. And as the men suffered in battle, so did these new family groups – often in ways that hurt the men as if they, too, were living entities. As we head toward Christmas, Hanukah, and the new year, let’s remember those men who gave so much in September 1862, who never again enjoyed a holiday season because of their sacrifice made around and in Antietam’s bloody Cornfield.

Endnotes:

[1] In comparison, losses at the Sunken Road are 5,500 (2,900 Union; 2,600 Confederate) while the total losses at the Burnside Bridge and the center/final Union attack total 3,470 (2,350 Union and 1,120 Confederate).

[2] These casualty figures and percentages are derived from Carman’s Antietam volume. Other sources list different numbers but all are roughly similar. Ezra A. Carman and Joseph Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign of 1862; Ezra A. Carman’s Definitive Study of the Union and Confederates at Antietam (New York: Routledge Books, 2008), pp. pp. 276-277; Ezra A. Carman and Thomas G. Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II: Antietam (California: Savas Beatie, 2012), Appendix Three, pp. 601-620.

[3] Confederate Veteran, Vol. 22, (December 1914), p. 555; http://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/texas/4th-texas-infantry/; United States War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), Series 1, Volume XIX, Pt. 1, p. 251, 928, 935 (hereafter listed as “OR”)..

[4] http://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/georgia/10th-georgia-infantry-regiment/.

[5] Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 263; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 198-200; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 874-875; Ronald H. Moseley, Ed. The Stillwell Letters: A Georgian in Longstreet’s Corps, Army of Northern Virginia (Mercer University Press, 2002), p. 46; Robert C. Krick, Lee’s Colonels (Dayton, Ohio: Morningside Bookshop Press, 1979). Antietam on the Web website, however, lists the 10th Georgia’s casualties as 90. If accurate, this would give the 10th Georgia 61% casualties and rank them Number Four on the list.

[6] http://civilwarintheeast.com/us-regiments-batteries/massachusetts/15th-massachusetts/.

[7] Robert E. Denney Civil War Medicine: Care & Comfort of the Wounded (New York: Sterling Publishing Co.,1995), pp. 155-167; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 311.

[8] http://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/georgia/18th-georgia-infantry/; http://antietam.aotw.org/officers.php?unit_id=580.

[9] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 244, 235, 928, 930; Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 229; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 91-93.

[10] Louis H. Manarin 15th Virginia Infantry (Lynchburg: H. E. Howard, 1990), pp. 2-3, 20-22; http://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/virginia/15th-virginia-infantry/

[11] Manarin, 15th Virginia, pp. 25-29; Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 263; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 198-200; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 874.

[12] Frederick Phisterer, New York in the War of the Rebellion, 3rd ed. (Albany: J. B. Lyon Company, 1912); http://civilwarintheeast.com/us-regiments-batteries/new-york-infantry/59th-new-york/; https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/infantry/59thInf/59thInfMain.htm.

[13] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 320; Correspondence of John Sedgwick, Vol. II (Carl and Ellen Battelle Stoeckel, 1902), pp. 158-159; Denney, Civil War Medicine, p. 156.

[14] Julian W. Hinkley A Narrative of Service with the Third Wisconsin Infantry (Wisconsin History Commission, 1912), pp. 1-49; http://civilwarintheeast.com/us-regiments-batteries/wisconsin/3rd-wisconsin/.

[15] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 494-495, 1022, 1053-1054; Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 240; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp.126-130.

[16] William Allan, Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and the Army of Northern Virginia 1862 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1995), pp. 332-333; http://antietam.aotw.org/officers.php?unit_id=626; https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=CNC0027RI.

[17] Walter Clark Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War (Goldsboro N. C.: Nash Brothers, 1901), p. 436; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 327, 482, 840, 872; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 309-311, 318-323.

[18] Benjamin F. Cook History of the Twelfth Massachusetts Volunteers (Webster Regiment) (Boston: Twelfth (Webster) Regiment Association, 1882), pp. 9-11, 23-24, 48-49, 59-60, 67-68.

[19] Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 219, 234; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 64-67.

[20] Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 227; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 88-89; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 923, p. 928, p. 932, pp. 937-938.

What a lot of great work, thanks David! FYI, AotW lists 90 members of the 10th Georgia Infantry, but 3 of them were not casualties. So 87 casualties listed. Of that number, 36 were casualties on South Mountain on Sept 14th or elsewhere on the Campaign, so not Cornfield casualties. What this shows is that I’m missing about 30 men who were casualties at Sharpsburg and probably another 20 on South Mountain 🙂 There’s always more to get to, right?

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind words! And you’re certainly right – there’s ALWAYS more to get to!

LikeLike

Great article and website! A few things to note, though….

The 4th Texas’ reported losses in the OR are 252 (44 killed, 207 wounded and 1 missing) at Gaines’ Mill, 99 (22 killed and 77 wounded) at Second Manassas, and 107 (10 killed and 97 wounded) at Antietam.

Col. Philip A. Work of the 1st Texas reported 170 losses out of 226 present, which would be 75%. However, as recorded by Ezra Carman, Work later wrote in an 1891 letter that on the evening of the 16th, two men from each of the twelve companies were detailed for foraging. Only nine of them returned to the regiment the following morning, so it actually went into action with only 211 men. Its losses were later revised to 186 (50 killed, 132 wounded, ad 4 missing), so taking that into account, the 1st Texas’ actual casualty percentage was 88%.

Also, I wouldn’t say that the 1st Texas fled from the field. Its casualty rate and Col. Work’s report indicate that it stood and fought until what few men left were ordered to withdraw by Work. Pvt. J. P. Cook later wrote that he got the order to fall back after firing his 34th round. Their Lone Star flag wasn’t abandoned either. The last man to grab them (possibly Lt. Robert H. Gaston, who was said to have been found lying dead across the flag) was shot down as they withdrew and lost in the confusion.

LikeLike

Thanks for your compliments and thoughts! You’re certainly right that both the engaged and the casualty numbers vary, depending on the source, so any listing will be inexact. I cite Carman’s numbers because they’re the most consistent and thorough numbers I’ve found – even though they’re not without error and his casualty figures are certainly too low in most cases. You’re also right that the 1st Texas didn’t abandon its flag–it was a loose use of that term on my part–and, like any regiment that lost its flag in action, this was most likely caused by the intense confusion of battle. I can understand your comment about the regiment not fleeing from the field because, as you note, rarely does one find such comments by first-hand sources. Nonetheless, the regiment’s considerable casualties and fact that it faced the bulk of Meade’s still-fresh division suggests that its retreat was unlikely to be a well-ordered, stubborn retreat. Thanks again for reading the article and visiting my site!

LikeLike

Pingback: The 6th Georgia in the Cornfield: Squeezed by a Deadly Vice | Antietam's Cornfield