D. R. Miller’s Cornfield was a long way from New Orleans’ docks and marshes, but for many “Louisiana Tigers” in Hays’ Brigade this deadly spot would become their final resting place…

By David A. Welker – Author of The Cornfield: Antietam’s Bloody Turning Point

In the war’s earliest days, only the New Orleans company raised by Captain Alexander White bore the famous moniker, the “Tiger Rifles.” White’s company quickly gained the attention of Major Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, seeking men for his 1st Special Battalion, Louisiana Volunteer Infantry (the 2nd Louisiana Battalion). Also joining Wheat’s battalion were Captain Robert Harris’s Walker Guards, Captain Henry Gardner’s Delta Rangers, and Captain Harry Chaffin’s Rough and Ready Rangers (later renamed Wheat’s Life Guards), then organizing at nearby Camp Davis, sited between the city’s Common and Gravier Streets at South Broad (modern Camp) Street. [1]

Major Wheat

The Tigers’ commander, Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, was a uniquely American mix of intelligence, daring, and rough adventurer. Born April 9, 1826 in Alexandria, Virginia his preacher father moved the family to New Orleans shortly afterward. Elected an officer in the 1st Tennessee Mounted Regiment at 20, Wheat served under General Winfield Scott in the Mexican War. Despite being elected to the Louisiana State Legislature in 1848 and admitted to the bar the following year, Wheat soon returned to military service – as colonel of a “filibuster” mercenary expedition in Cuba. Now essentially a professional soldier of fortune, Wheat in 1855 accepted a brigadier general of artillery’s commission from the Mexican State of Guerrero to campaign against Santa Anna and in 1860 travelled to Italy to serve under Garibaldi in the Campaign of 1860. Upon learning of Louisiana’s secession Wheat returned home, offering his services to the Confederacy.

The roughly 500 men joining Wheat’s command were a similarly tough crew. Many were foreign-born, particularly Germans and Irish Americans, and nearly all emerged from New Orleans’ rough working classes. This was particularly true of those coming from the wharves and docks, who made up one of the Nineteenth Century’s lowest social classes and performed the most dangerous, dirty, and undesirable work available. One observer described Wheat’s men as “the lowest scum of the lower Mississippi…adventurous wharf rats, thieves, and outcasts…and bad characters generally.” Regardless, many men had already served in local militias or as filibusters in various overseas expeditions. [2]

An original Tiger hat

None were tougher, however, than White’s original Tiger Rifles company. Captain White himself was a smuggler and gambler who had served prison time, despite his Mexican War Navy service and recent efforts to reform as a respectable married steamer captain. Recruited around his steamer crew, the Tiger Rifles were soon outfitted in distinctive Zouave dress—modeled on French North African units—of blue vests, red tasseled fezzes, and their signature “’Wedgwood blue and cream’ one-and-one-half-inch vertically striped cottonade ship pantaloons.” They painted distinctive pictures and mottos on their hats, such as one depicting a fist fighter and the words “Before I was a Tiger,” while others read “Tiger Bound for Happy Land,” “Tiger Will Never Surrender,” “A Tiger Forever,” “Tiger in Search of a Black Republican,” or “Lincoln’s Life or a Tiger’s Death.” Their flag was the very model of irony, depicting a “gamboling lamb” with “Gentle As” written above. [3]

Wheat’s colorful Tigers’ original uniforms

By May 1861 the battalion elected Wheat its major, joining other Louisiana regiments training at Camp Moore. There the five companies received their weapons, a mish mash seized from the Baton Rouge Federal armory in January 1861 including ancient Model 1816 flintlock conversions, Connecticut-made Model 1841 “Mississippi” Rifles, and Model 1842 muskets. Most lacking bayonets, the men carried instead large private purchase Bowie knives.

On June 6, 1861 Louisiana officially recognized Wheat’s elected rank and accepted his unit as the “1st Special Battalion, Louisiana Volunteers. Although Wheat’s political maneuvering to grow the unit and become the 8th Louisiana Infantry Regiment failed, the Battalion nonetheless brought a sixth company into its ranks, Captain Jonathan W. Buhoup’s Catahoula Guerrillas. Five days later, Wheat’s five full-strength companies boarded a train headed to Virginia for what everyone knew would be the one and only battle deciding this still-new war. [4]

Got something to say about our striped pants or socks? I thought not…

Arriving in Northern Virginia, Wheat’s Tigers were assigned to Brigadier General Nathan “Shanks” Evans’ Seventh Brigade in the Confederate Army of the Potomac. By dawn on July 21, 1861 the Tigers were posted on the far-left flank of Beauregard’s line along Bull Run, on Matthews’ Hill, where they were the first to confront advancing Federals under Colonel Ambrose Burnside. Greatly outnumbered, Wheat daringly ordered his Tigers to charge – briefly stalling the Union attack. Though scoring their first victory of the war, it had cost the Tigers 11 dead, two missing and 38 wounded – including Major Wheat, shot through the lungs. Though now proven fighters in battle, it was their behavior in camp during the ensuing months that cemented the Tigers’ reputation. [5]

Assigned now to Brigadier General Richard Taylor’s First Louisiana Brigade, part of Major General Richard Ewell’s Division, they settled into “Camp Florida” near tiny Centreville, Virginia. With time to spare Wheat’s men again revealed their street tough nature, which reached a crescendo when Tigers Dennis Corcoran and Michael O’Brien were executed on December 9, 1861, following a drunken row in camp which ended when the 7th Louisiana’s Colonel Hays drew a pistol on Corcoran (the executed men are buried today in the Centreville Episcopal Church’s adjacent graveyard). As their brigade commander noted “so villainous was the reputation of this battalion that every commander desired to be rid of it.” Nonetheless, soon the entire brigade adopted the Tiger moniker, popularly becoming “the Louisiana Tiger Brigade.” [6]

Assigned now to Brigadier General Richard Taylor’s First Louisiana Brigade, part of Major General Richard Ewell’s Division, they settled into “Camp Florida” near tiny Centreville, Virginia. With time to spare Wheat’s men again revealed their street tough nature, which reached a crescendo when Tigers Dennis Corcoran and Michael O’Brien were executed on December 9, 1861, following a drunken row in camp which ended when the 7th Louisiana’s Colonel Hays drew a pistol on Corcoran (the executed men are buried today in the Centreville Episcopal Church’s adjacent graveyard). As their brigade commander noted “so villainous was the reputation of this battalion that every commander desired to be rid of it.” Nonetheless, soon the entire brigade adopted the Tiger moniker, popularly becoming “the Louisiana Tiger Brigade.” [6]

The Tigers’ new uniforms

In spring 1862 Wheat’s battalion and the Tiger Brigade joined Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in his Shenandoah Valley Campaign in battles at Front Royal, First Winchester, and Port Republic. Wheat’s four-company battalion—now minus the Catahoula Guerrillas, which fled to organizational safety in the 7th Louisiana—replaced their worn Zouave uniforms for the Louisiana Brigade’s dress, grey jean cloth jackets and pants trimmed in black. [7]

Wheat’s commission, found on his body after Gaines Mill

Transferred with Jackson’s army to defend Richmond from Union General McClellan’s advancing host proved costly. Colonel Wheat was killed during the June 27, 1862 Battle of Gaines Mill and combat, disease, and desertion had whittled the Special Battalion down to only 60 officers and men. Lacking Wheat to champion them administratively, what remained of the original Tigers was merged into the 1st Louisiana Zouave Battalion, essentially “reorganized out of existence.” Those few original Tigers who remained to reach Sharpsburg on September 17th participated with Starke’s Brigade in driving two of Gibbon’s Wisconsin regiments back into the Cornfield. For better or worse, the Special Battalion’s reputation and name had shifted to its former brigade – Taylor’s Brigade became the Louisiana Tiger Brigade.

Brigadier General Harry T. Hays

The Louisiana Tiger Brigade now consisted of the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 14th Louisiana Infantry, along with the Louisiana Guard Artillery. With General Taylor’s July 1862 transfer west, the 7th Louisiana’s General Harry T. Hays assumed formal command but because Hays remained away recuperating from a shoulder wound sustained at Port Republic, the 5th Louisiana’s Colonel Henry Forno assumed de facto command. [8]

Moving north as part of Lee’s 1862 Virginia Campaign, the Tigers’ next saw significant combat during the Second Battle of Manassas. Posted on August 29 along the famous unfinished railroad cut, after several waves of Union assaults expended their ammunition and with another blue wave coming, the men grabbed rocks lining the railroad bed – hurling the stones blunted the Federal attack. Still, the Tigers’ lost 37 killed and 95 wounded and command shifted again when Colonel Forno was wounded late in the day, placing the 6th Louisiana’s Colonel Henry B. Strong in charge. Moving east on August 31 brought them into action again during the rain-soaked fight at Chantilly, after which the Tigers finally enjoyed some well-earned rest. [9]

Scene of the Tigers’ famous rock fight, Second Manassas’ Unfinished Railroad cut

But by September 3 the Tigers were again moving north, this time heading into Maryland. Taking part in the comparatively easy capture of Harpers Ferry on 15 September, General Hays finally rejoined the Tigers on the 16th in time to lead them back into Maryland and rejoin Lee’s army gathering at Sharpsburg by nightfall. [10]

Hays’ Tiger Brigade halted behind the Dunker Church just as Hood’s Division received its first fire in what was soon to become the Battle of Antietam. Meanwhile, as units arrived General Jackson posted them in a defensive position facing north on the flanks of the Hagerstown Pike. Stonewall put his own former command, Jackson’s Division, in the first line, while Ewell’s Division deployed behind and on the left flank of Jackson’s position. Out in front of the entire position on a small knoll were six artillery pieces of Poagues’ Battery. Behind this strong division-plus sized formation was Hays’ Brigade, and in their rear—around the Dunker Church—Lawton’s and Trimble’s Brigades. Stuart’s cavalry held the two or so miles between Jackson’s left and banks of the Potomac River.

Tigers’ position overnight, at dawn

While in the West Woods the Tigers’ suffered their first casualty at Antietam near dark when Union artillery responded to the long-range fire of Poague’s battery, supporting Wofford’s infantry brigade then engaged in Miller’s Cornfield. A random shell slammed into the woods, killing the 9th Louisiana’s Lieutenant A. M. Gordon, after first tearing off both of his legs. Nonetheless, the Tigers and Jackson’s other troops settled down for a fitful night amidst drizzling rain and intermittent skirmishing. The 14th Louisiana’s William P. Snakenberg barely slept that might, however, troubled by a premonition of his wounding in the coming battle. Fighting off an inclination to request his colonel keep an eye on him, fearing he might be thought a shirker, Snakenberg instead shredded personal letters and destroyed anything he feared falling into the enemy’s hands, ending his uneasy night by consuming all his remaining food. [11]

Around 10:00 that evening Jackson replaced Hood’s exhausted command with Lawton’s Division, which moved forward through the dark to form Stonewall’s salient opposing the Cornfield. Lawton’s former brigade, led by Colonel Marcellus Douglass, posted on the left facing north, while Trimble’s Brigade, commanded by Colonel James A. Walker, moved into position on the right. With this small force Jackson would do great things, come dawn. [12]

Union General Joseph Hooker, overseeing McClellan’s opening attack on the Confederate left flank and the Federal I and XII Corps, used the darkness to plan his assault for dawn. Two divisions of his I Corps would open the attack, both aiming for the small, white Dunker Church as a shared objective, to take the ridge Jackson held and break the Southern left. Under this plan Brigadier General Abner Doubleday’s Division would drive straight south along the Hagerstown Pike, while Ricketts’ Division would advance diagonally across D. R. Miller’s fields. [13]

As sunrise revealed the first stirrings of Hooker’s attackers, Confederate artillery on Nicodemus Heights, to the Tigers’ left, opened on the enemy. Rather than deterring the Federals, this fire only accelerated their advance. As the Tigers watched from the relative safety of the West Woods, Lawton’s and Trimble’s Brigades facing the southern end of the Cornfield opened on Yankee attackers.

Although only one brigade of Ricketts’ force, Brigadier General Abram Duryee’s New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians, reached the southern end of the Cornfield, their determined attack was wreaking havoc on General Lawton’s defense. Worse, Lawton soon discovered that his brigade faced not only Duryee in front but Yankees remaining in the East Woods to his right—Brigadier General Truman Seymour’s men—and portions of Doubleday’s advance, the left-most of Brigadier General John Gibbon’s Iron Brigade, as well. Worse, in shifting to meet these threats a 120-yard gap had appeared between Lawton’s and Trimble’s Brigades, in the very center of his line. If this wasn’t plugged soon, Union attackers would surely plunge into it and shatter his formation. Quickly, Lawton sent an aide to find General Hays. [14]

I response, Hays’ 550 or so Tigers swept out of the woods, north of the Dunker Church, and onto the field. Confused by the apparent ambiguity of Lawton’s order sending them to “a point in our lines yet unoccupied,” Hays marched his men uncertainly forward and dispatched his assistant adjutant general, Captain John H. New, to sort out where they were supposed to be. After three moves General Lawton finally settled things by posting Hays behind Lawton’s Brigade, in reserve. Though in the rear, this spot was deadly enough. [15]

I response, Hays’ 550 or so Tigers swept out of the woods, north of the Dunker Church, and onto the field. Confused by the apparent ambiguity of Lawton’s order sending them to “a point in our lines yet unoccupied,” Hays marched his men uncertainly forward and dispatched his assistant adjutant general, Captain John H. New, to sort out where they were supposed to be. After three moves General Lawton finally settled things by posting Hays behind Lawton’s Brigade, in reserve. Though in the rear, this spot was deadly enough. [15]

“We lay in that position with a fire from three Yankee batteries and one from a battery of our own answering, firing over our head, besides a fire of Infantry on the Brigade in front of us,” the 6th Louisiana’s Lieutenant Ring later told his wife. “I thought, darling, that I had heard at Malvern Hill heavy cannonading, but I was mistaken.” For the 5th Louisiana’s Captain Fred Richardson these exposed moments brought a particular horror and he recalled “…a shell from the enemy plunged through my poor camp, passing first though the body of poor William [Canfield], then cut off the leg of John Fitzsimmons, then both feet of D[avid] Jenkins, and passed through my poor friend Nick [Lieutenant Canfield, William’s brother], entering at the small of the back, coming out at the breast, tearing out and exposing his heart…in one shot I lost three killed.” Another such shell killed the 5th’s Charles Behan – on his 18th birthday. [16]

The brigade’s earlier wanderings had confused Colonel Walker, who assumed the Tigers were advancing on his left and so ordered Trimble’s Brigade forward into the corn after Duryee’s now-retreating Yankees. Though slow to respond, soon the whole of Trimble’s Brigade pressed forward until finding Matthews’ and Thompson’s Union batteries; opening instantly, they forced Walker to halt. Then, still believing Hays’ Brigade was advancing and seeing Union reinforcements heading straight at him though the corn, Walker retired Trimble’s Brigade – yielding the eastern end of the Cornfield. [17]

Lawton’s Brigade, too, pushed into the gap created by Duryee’s retreat, while to its rear the Tigers began advancing in response to an earlier plea for help from Colonel Douglass. But before the Tigers could reach them, Lawton’s men were halted and began falling back, taking heavy infantry fire to both flanks—exposed by their too rapid advance—and from artillery in their front. But what really stopped and drove back Lawton’s Brigade was the arrival of a fresh Union brigade ahead in the corn. With both Lawton’s and Trimble’s Brigades retreating, the Confederacy had lost hold of the Cornfield. [18]

It apparently had taken little urging to get the five Tiger regiments—the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 14th Louisiana—moving forward because doing so offered relief from the deadly Federal artillery fire. By the time Hays’ Tigers reached Lawton’s line—which might have been moving backward by then—the Louisianans were alone. Still, on the Tigers pressed, crossing the southern fence and pressing deeper into the deadly Cornfield.

It apparently had taken little urging to get the five Tiger regiments—the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 14th Louisiana—moving forward because doing so offered relief from the deadly Federal artillery fire. By the time Hays’ Tigers reached Lawton’s line—which might have been moving backward by then—the Louisianans were alone. Still, on the Tigers pressed, crossing the southern fence and pressing deeper into the deadly Cornfield.

The fresh Union force that had driven away Lawton’s men was Brigadier General George L. Hartsuff’s Brigade, commanded now by Pennsylvanian Richard Coulter in place of the just-wounded general. Intended as the centerpiece of Ricketts’ Division’s opening attack, Hartsuff’s removal had stalled the brigade’s advance but once squared away it pressed confidently into the corn. So swift and successful had its drive become that Coulter recalled some of his 12th Massachusetts skirmishers and Thompson’s Battery had limbered up its guns to join the advance. In an instant, though, Coulter’s command was robbed of its success as Hays’ Tigers came over a rise and through the shattered corn at the double-quick. [19]

Seeing the Tigers advancing with speed and determination, Coulter decided to secure a better position than standing in this open field. Ordering his two left-most regiments to “Right wheel, March!” had the 83rd New York and 13th Massachusetts swing right, moving like a barn door hinged on the right. Coulter’s line now resembled a huge “L,” facing south and west – and into the center of this position marched Hays’ Tigers. [20]

“The skirmishers had all disappeared,” recalled the 13th Massachusetts’ Austin Stearns, “we boys thought we were to go for them with the bayonet, and we fixed the same. Neither side, with the exception of the skirmishers and batteries had fired, but now it was time for the infantry to take their turn, and we were getting uncomfortably near.” [21]

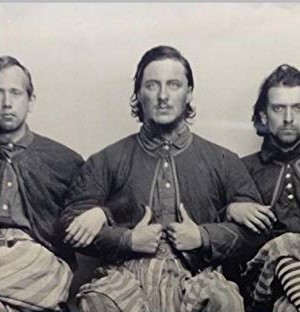

8th Louisiana Tigers

Hays’ Brigade reached a point where it could go no farther on momentum alone. Having passed beyond Lawton’s right flank, Yankees were now on their right and blocking their path in front. Halting the men, General Hays ordered his brigade to open fire. “The rebs fired first but we being so near, many of the balls went over our heads, but still many took effect,” Corporal Sterns added. Now commenced one of the deadliest firefights of this most deadly day. It was 6:40 a.m. [22]

Stuck in a terrific crossfire by being caught in Colonel Coulter’s L formation, the Tigers suffered greatly trying to drive away Hartsuff’s Brigade. “The balls were coming so thick at this time that I feared I should never be able to get off the field,” recorded the 8th Louisiana’s Lieutenant George Wren. As the Tigers’ ranks thinned, Wren discovered “…but three out of eighteen men [in my company] standing, several had just fallen wounded and in one moment more a ball passed through the calf of my left leg.” Private Snakenberg found his premonition confirmed when just after loading his rifle “I felt something burn me and seemed to paralyze my left side. I stood still trying to think of the matter, not knowing I was wounded, and…pulled my clothes away from my body, when everything seemed to turn green to me and I staggered for 20 feet and fell.” Former brigade commander Colonel Strong of the 6th Louisiana, too, was killed, atop his white horse—which also fell—and officer and mount passed from this world as a pair. [23]

6th Louisiana Tigers

The 6th Louisiana’s Lieutenant George Ring described the Tigers’ Cornfield fight to his wife, “We…commenced firing upon the enemy who were in front of a wood about two hundred yards off, protected by a battery. We stood there about a half an hour and found ourselves cut all to pieces.” “I was struck with a ball on the knee joint while I was kneeling by Col. Strong’s body, securing his valuables. I got another ball on my arm and two on my sword in my hand, so you can see I have cause to thank God that he has protected me in this great battle.” William Snakenberg found slightly more temporal help when his friend Mike Clark helped him away to find a field hospital. [24]

Hay’s Brigade had held on as long as possible but soon found its position literally melting away. When Confederate reinforcements of Hood’s Division appeared, the Tigers eagerly retreated toward the Dunker Church and their original position. There General Hays reported gathering only 40 men, although that number certainly grew as others found their way back to the brigade (by the next morning this number had risen to 90, despite additional casulties suffered on the 17th). Here they remained from roughly 9:30 until 12:15 as the fighting continued in the Cornfield. Their saving reinforcements of Hood’s Division meanwhile were similarly repulsed and similarly fell back beyond the church. McLaw’s Division and other Confederate reinforcements arrived to drive away Major General Edwin Sumner’s Union II Corps attackers, as other of Jackson’s troops drove back Brigadier General George Greene’s Division. [25]

Hays’ Tigers’ Final Position at Antietam

Sometime before 1:00, Hays’ Tigers went forward once more, advancing to support Hood’s Division’s hold on the West Woods immediately west of the church. Despite Hays’ implied aggressiveness claimed in his Antietam report—“I moved again to the front…”—more likely his command was ordered there in response to the growing line of fresh Federal VI Corps brigades and artillery which was poised to attack the West Woods yet again. [26]

Although this was not to be, the massed Yankee guns incessantly shelled the Confederate position, causing the Tigers additional suffering and casulties. Among these was the 6th Louisiana’s Captain H. Bain Ritchie, who had initially assumed regimental command upon Colonel Strong’s death. As Lieutenant Ring wrote “We remained in the front exposed to frequent shelling from the enemy until 5 o’clock p.m., when we fell back to a less exposed position. [27]

The losses Hays’ Louisiana Tigers suffered at Antietam was unimaginable. The brigade recorded 45 killed—including 10 officers—and 289 wounded, as well as two missing, a total of 336 casulties for its trip into the Cornfield. Among its regiments, the 8th Louisiana had fared the worst, incurring 103 casulties, although the 6th and 7th Louisiana suffered the most killed with 11 each. The 6th lost all twelve of its company-grade officers—five killed outright—and its color bearer, Sergeant John Heil. [28]

Although despite this cost they had failed to drive Hartsuff’s Brigade from the Cornfield, the Tigers had nonetheless torn the once-fresh Yankee unit to pieces, making its own retreat inevitable. The Tigers’ too shared shockingly high losses with Hartfuff’s Brigade, particularly his 12th Massachusetts, which suffered 76 percent casualties—the highest for any Union regiment at Antietam. Perhaps more significantly, the Tigers had cleared the Cornfield’s eastern end, which eased Hood’s Division’s efforts in the Cornfield. [29]

Despite its casulties suffered at Antietam, much fighting remained ahead for Hays’ Louisiana Tiger Brigade. Although in reserve at Fredericksburg in December 1862, during the Battle of Chancellorsville the Tigers and Early’s Division endured more combat in the May 4, 1863 fight for Banks’ Ford. During Lee’s second invasion of the North, Hays’ Louisianans fought at the June 13-15 1863 Second Battle of Winchester, notably seizing West Fort, leading General Ewell to rename the spot “Louisiana Heights” in the Tigers’ honor. [30]

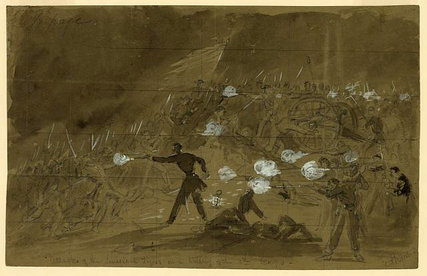

Hays’ Tigers (left of the firing officer) at Gettysburg

At Gettysburg, Hays’ Tigers held the Confederate right flank striking Cemetery Hill during the battle’s second day. During the November 7, 1863 Battle of Rappahannock Station nearly half of Hays’ Brigade was captured.

Entering the 1864 Overland Campaign with a new stock of men—Lee’s May 1864 army reorganization merged them with the Second Louisiana “Pelican” Brigade—the Tigers fought at both the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, where General Hays was wounded by a shell that ended his Civil War combat service.

The Tigers, now commanded by the 14th Louisiana’s Brigadier General Zebulon York, joined Jubal Early’s drive down the Shenandoah Valley to threaten Washington D.C., taking part in both the July 9 Battle of Monocacy in Maryland and the July 12 attack on Fort Stevens. In Washington, D.C. When York was wounded during the September 19, 1864 Third Battle of Winchester, Brigadier General William R. Peck took charge, leading the Tigers in rejoining the Army of Northern Virginia in the works defending Petersburg. By April 1865, the Tigers had given their all and, like Lee’s other troops, faced the inevitable and surrendered. But their service to Louisiana and other causes wasn’t done.

After recovering from his Spotsylvania wound, Harry Hays returned to New Orleans to rebuild his life. Pardoned by President Andrew Johnson, Hays was appointed Sheriff of New Orleans Parish and formed the Hays Brigade Relief Society. Working to support Confederate veterans by offering financial and social aid, much like other such groups that followed, it frequently held open meetings and fund-raising events. [31]

After recovering from his Spotsylvania wound, Harry Hays returned to New Orleans to rebuild his life. Pardoned by President Andrew Johnson, Hays was appointed Sheriff of New Orleans Parish and formed the Hays Brigade Relief Society. Working to support Confederate veterans by offering financial and social aid, much like other such groups that followed, it frequently held open meetings and fund-raising events. [31]

Several Irish Tiger Brigade veterans joined other members of the patriotic Irish Fenian Brotherhood from across the reunited nation in traveling to the Canadian border. Formed into the “New Orleans Company (Louisiana Tigers), they joined other Irish units crossing into Canada as part of an effort to seize territory to exchange for Irish freedom. Taking part in the June 2, 1866 Battle of Ridgeway, their retreat and arrest failed to free Ireland but nonetheless prompted Britain’s Parliament to advance Canadian Commonwealth. [32]

The Battle of Ridgeway

On July 30, 1866 riots erupted in New Orleans when white locals attacked Republican and African American leaders who had gathered to revise Louisiana’s constitution, upset by implementation of racially divisive “black codes” restricting Freedmen’s newly won rights and freedoms. 48 people were killed before Sheriff Hays and his deputies—nearly 100 of whom were Tiger veterans, drawn in part from members of the Relief Society—helped quell the riots. [33]

Most modern Americans are more likely to connect the Louisiana Tigers with today’s Louisiana State University football program or the university’s many other excellent sports teams. Earning numerous national titles and other accolades, these athletes can trace the origin of their school mascot to the fighting spirit of the Tiger Rifles of 1861 and Hays’ Louisiana Tiger Brigade of 1862-1865. Like today’s sports champions, their Tiger forebears merged grit and dedication to earn a reputation as some of the nation’s finest fighters. And nowhere was that fighting spirit tested more thoroughly than in Antietam’s deadly Cornfield… [34]

Most modern Americans are more likely to connect the Louisiana Tigers with today’s Louisiana State University football program or the university’s many other excellent sports teams. Earning numerous national titles and other accolades, these athletes can trace the origin of their school mascot to the fighting spirit of the Tiger Rifles of 1861 and Hays’ Louisiana Tiger Brigade of 1862-1865. Like today’s sports champions, their Tiger forebears merged grit and dedication to earn a reputation as some of the nation’s finest fighters. And nowhere was that fighting spirit tested more thoroughly than in Antietam’s deadly Cornfield… [34]

Endnotes:

[1] Schreckengost, Gary. The First Louisiana Special Battalion: Wheat’s Tigers in the Civil War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2008), pp. 34-35.

[2] Schreckengost, The First Louisiana, pp. 35-36.

[3] Schreckengost, The First Louisiana, pp. 37-42.

[4] Schreckengost, The First Louisiana, pp. 42, 46-47. Chaffin’s Rough and Ready Rangers remained behind because it had failed to reach full enrollment.

[5] Bearss, Ed. First Manassas Battlefield Map Study (Lynchburg: H. E. Howard Publications), p. 100.; Hennessy, John The First Battle of Manassas: An End to Innocence (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2015), p. 58; The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume XIX, Parts 1 and 2. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1887 (Hereafter OR), pp. 559, 561.

[6] Daily Delta, New Orleans, 6 January 1862; Schreckengost, The First Louisiana, pp. 84-87; Jones, Terry L. Lee’s Tigers Revisited: The Louisiana Infantry in the Army of Northern Virginia (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017), p. 8.

[7] Schreckengost, The First Louisiana, pp. 89-91.

[8]https://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/louisiana/1st-louisiana-zouave-battalion/.; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt.1, p. 967; Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, p. 178-180. The Special Battalion continued serving until 1864, though in reserve and rear-guard duties, and was finally dissolved in December 1864.

[9] Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, p. 192-195; John Hennessy Second Manassas Battlefield Study, Second Edition (Lynchburg: H.E. Howard Publications, 1991), p. 471.

[10] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 967, 978.

[11] Joseph L. Simpson “Official Report of Lieut. Simpson, Batty. A, 1st Penn. Artillery, Engagements of September 16th & 17th, 1862” (unpublished in OR) and Ransom “Official Report,” Joseph Hooker military papers, 1861-1864, Box 9, Huntington Library, San Marino, California; Carman, Ezra and Joseph Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign of 1862; Ezra A. Carman’s Definitive Study of the Union and Confederates at Antietam (New York: Routledge Books, 2008), p. 208; Carman, Ezra and Thomas Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign of 1862, Volume II: Antietam (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2012), pp. 36-38, Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, pp. 203-204.

[12] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 922, 976-977.

[13] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 217-218.

[14] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 217-218, 258-259, 248-249, 255-257.

[15] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 978-979.

[16] Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 218, p. 220; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 61-63; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 978; Gannon, James P. Irish Rebels, Confederate Tigers: the 6th Louisiana Volunteers, 1861-1865. (Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing Co., 1998), pp. 135-136; Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, pp. 203-204.

[17] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 977; Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 218; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp.61-63. Although Walker, in his OR, claims unnamed reinforcements—probably Hays’ Brigade—that had in part inspired his advance “gave way under the enemy’s fire and ran off the field” and forced the retreat of Trimble’s Brigade, no other accounts corroborate these accusations.

[18] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 975-976.

[19] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 258-259, 265-266.

[20] Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 234; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 64-65.

[21] Stearns, Austin C. and Arthur Kent, Ed. Three Years with Company K (London: Associated University Press, 1976) p. 127.

[22] Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 234; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 64-65; Stearns, Three Years with Company K, p. 127; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 978-979.

[23] Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, pp. 204-206; George Lovick Pierce Wren Diaries, Box 1, Folder 3, Emory University.

[24] Gannon, Irish Rebels, p. 136; Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, pp. 204-206.

[25] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 972.

]26] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 972; Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, pp. 206-207.

[27] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 972; Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, pp. 206-207.

[28] Gannon Irish Rebels, pp. 135-136; Jones Lee’s Tigers Revisited, pp. 204-206.; OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 978-979.

[29] Stearns, Three Years with Company K, p. 130; Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 224; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 79-83.

[30] Sears, Stephen W. Chancellorsville (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1987), pp. 410-417; Pfanz, Harry Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), pp. 235-239, 256-258.

[31] The Times-Democrat, New Orleans, Louisiana, 17 June 1866; The Times-Picayune, New, Orleans, Louisiana, 9 July 1866.

[32] Vronsky, Peter Ridgeway: The American Fenian Invasion and the 1866 Battle That Made Canada (Toronto: Penguin Group (Canada), 2011), pp. 45, 58, 211.

[33] Hollandsworth, Jr. James G. An Absolute Massacre: The Race Riot of July 30th, 1866 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001).

[34] LSU officially traces the origin of the tiger mascot to a live tiger acquired in 1924, as well as a subsequent 1936 big cat named “Tiger Mike” in honor of athletic trainer Mike Chambers (long before the recent uproar over animal mistreatment depicted in the “Tiger King” documentary, of course). Regardless, it remains clear that Louisiana’s earliest association with tigers–hardly a native animal–dates to the 1861 Tiger Rifles, so the university’s acquisition of two tigers and Chambers’ “Tiger Mike” nickname all trace their origin to the Civil War Tigers.

Readers: Ron Anglin shared this story of his Louisiana Tiger ancestor:

John Francis McCarroll, 7th Louisiana, at the battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg

September 17, 1862

At sunrise on the morning of September 17, 1862, John found himself a private in the ranks of Company K of the 7th Louisiana Infantry. His company was attached to Brigadier, General Harry T. Hays (1820-1876), First Louisiana Brigade, which was occupying a reserve position in the West Woods near an open field on the Miller farm. This Brigade was known as the “Louisiana Tiger.” having taken the name from the original battalion commanded by Roberdeau Wheat. The battle he was about to be engaged is known as the Battle of Antietam. It is also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg by the Confederates. The battle fought on the 17th between Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Union General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. This battle would be part of what would be called the Maryland Campaign and was the first field army-level engagement in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War to take place on Union soil. It would turn out to be the bloodiest day in the United States military history, with a combined total of 22,717 dead, wounded, or missing.

John Francis was born in Livingston Parish, Louisiana, in 1841, the oldest son of John and Martha Richardson McCarroll.1 The McCarroll’s were of the Scotch Irish ancestry, first settling in Pennsylvania in colonial times.2 From there, they moved south through Virginia, Kentucky, to Tennessee, where his father John senior was born in 1814. John Sr. moved to Livingston, Parish (now Tangipahoa) sometime in the 1830s. On October 29, 1836, he served as a witness to a land sale.3 And on May 26, 1838, he was the executor of the estate of a man by the name of Thomas Kennedy of St. Heliena Parish.4 What their connection was I don’t know at this time. In 1840, or thereabouts John, Sr.. married Martha Richardson.5 John and Martha had a total of six children: John born 1841, James in 1845, Amanda in 1846, Levinia in 1847, Nancy in 1848, and Samuel born in 1850.6

In 1844, John Sr. was named in the Will of his wife’s parents Samuel Richardson and Rachel Hamilton.7 On April 1, 1845, John St. purchased 80 acres of land in the NW 1/4 of the SE 1/4 of the SE 1/2 of Section 28, Township 7 south, Range 8 east, in the Parish of Livingston in the Greensburg District, about 3 1/2 miles from Ponchatoula Station, from his father-in-law.8 John Sr. must have been a prosperous farmer because, on October 17, 1849, he sold two slaves, one a negro woman named Rozina age 18 years and her child Harriett age 18 months for the sum of $700.9

On November 11, 1855, John Sr. leaving the job raising six children to his wife and, most likely, his oldest son.10 Until his father’s death, John Francis must have spent many hours exploring and hunting in the vast virgin forest near his home. (Later the McCarroll’s would become the great lumbermen of this part of Louisiana, but that’s another story). With the death of John Sr, most of the farming must have fallen on his oldest sons’ shoulders. John listed himself as a farmer in the 1860 census. Sometime during 1860, he found time to marry Katherine (Katie Flack, born March 25, 1850, in New Orleans died May 1, 1925, Hammond, Louisiana).11 It would appear that Katie was only ten years old at the time of there marriage. In 1866, they had their first child Joseph Leonard, died April 1905. Joseph would later marry Nora A Powell born October 1871 died ca 1911; from there marriage, they had four children: Frank James 1891, Katherine Florence Anglin McDonald 1895-1988 (my grandmother); Ward E. 1901 and Clyde Ward, died while on a chain gang ca. 1910 somewhere around Bagdad, Fl.

When the war came, John must have seen many of his close friends rush to join units forming for the defense of the South. He was twenty years old when he enlisted in Ponchatoula, Louisiana, inducting in April 1862 at Camp Moore, an extensive training area not far from his home in Livingston Parish.12 By the time he reached the west Woods on Miller’s farm, he was already a seasoned combat veteran from Stonewall Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign. He saw his first combat on May 23, at Front Royal, Virginia, and then again on the 24th at the battle of Middletown, Virginia. On June 8 he was at the battle of Cross Keys, and on the 9th at the fight at Port Republic, Virginia.

After these fights in the Shenandoah Valley, Jackson’s Corps. was given a short breathing spell before being ordered to tie up with Lee’s main army at Leesburg, Virginia. Jackson’s corps crossed at White’s Ford on the Potomac River the night of September 5, 1862. John’s stay in Maryland wax short-lived because Brig, General Harry T. Hays, First Louisiana Brigade, was ordered to recross the river at Light’s Ford on the 11th. Hay’s Brigade was being used as reserves for the fight, then taking place at Harper’s Ferry. After the battle at Harpe’s Ferry, Jackson had most of his corps make a forced march back to Sharpsburg to bring Lee’s army back together. It was here on the night of the 16th that the First Louisiana brigade bivouac in the West Woods near the Dunker Church, with their rifles ready.

Neither armies sleep well that night. All night long shots were fired by the pickets of both sides who camped close together. We don’t know what most of these men were thinking, but I believe it would be safe to assume they were thinking of the impending fight, their families, and how they would come out of this battle.

The fighting initially commenced on the 17th in John’s area when the 105th New York Volunteers of General. Abram Duryea’s Brigade, emerging from the southern edge of the Cornfield, came under the direct fire of the Confederate infantry located in the open field beyond. Within half hour, the 105th New York was forced back by Trimble’s Confederates, along with the remainder of Duryea’s Brigade. Next to arrive was the 13th Massachusetts of General. George L. Hartsuff’s Brigade, also of Ricketts’s division.

Although the waiting may have seemed an eternity to the members of Hays’s Brigade, it did not last longs. At approximately 6:45 am, the Brigade received orders to advance. Hays’s Brigade covered the ground from the edge of the East Woods to a point opposite the center of the Cornfield. Lawton’s Brigade extended the line towards the Hagerstown Pike on the left. As the two Brigades approached the Cornfield, they could see, dimly visible through the smoke, an equally long line of enemy infantry coming through the remains of the Cornfield.

Enemy rifle fire intensified. The crack of a single rifle soon was lost in the deafening roar of hundreds firing at the same moment. Soon men were dropping all around. The slaughter was said later to be appalling. As Hays’s Brigade finally reached their assigned place with destiny, the Cornfield. At first, the Union forces fell back through what had once been a 30-acre Cornfield, now a mangle of dead and dying men. It was more like the floor of a slaughterhouse than of a cornfield about to be harvested. Then as if someone had opened a valve, a devastating counterattack was made by fresh northern troops. Ammunition was running low, and casualties were staggering, but the Louisianan’s held on until they could hold no longer. The order passed through the ranks for what was left of Hays’s Brigade to fall back. Other Confederate Brigades were waiting for their place in the killing field. Thus ended the brief participation of Hays’s Louisiana Tigers at what was to be called the deadliest day in American history. Engaged in direct contact with the enemy for all of fifteen or twenty minutes, loss of life during that period was staggering.

General Hays would state in his official report. My Brigade, at the time, did not number over 550 men. So exposed was our position to withering fire from several batteries, and the Union infantry in front, over half my command, was lost in a short period. Having lost more than one-half (323 killed, wounded, and missing), that on General Hood’s Brigade coming up as re-enforcement, I was obliged to retire.

After making the final count, the First Louisiana Brigade lost in those few minutes, ten officers killed, 35 enlisted men killed, 46 officers wounded 243 enlisted men wounded, and two missing. Of these two men missing one of them was John Francis McCarroll. John captured on the day of the battle and held prisoner until November 10, 1862, when he was exchanged in a prisoner of war trade at Aiken Landing, Virginia. By December 13, 1862, he was back with his company.

LikeLike

How do I contact Mr Ron Anglin? I’m related to John Francis McCarroll, and would like to speak to Mr Anglin about him

LikeLike

Can you get me in touch with Ron Anglin? I’m related to John Francis McCarroll , and would like to learn more about him.

LikeLike

Just want to note that the photo of the 3 tigers “Got something to say about our striped pants or socks? I thought not…” are of 3 modern day reenactors. It has been gaining a lot of attention in various places as an original.

LikeLike

Thanks for adding that. I suspected it might be the case, which is partly why I added the humorous caption.

LikeLike