The 5th Virginia’s Ezra Stickley awakened and realized the firing had picked up considerably. Gathering up his gear…Ezra discovered he’d misplaced the right glove of his newly-purchased pair, a loss that troubled him considerably. Within the hour Ezra would be troubled by a much greater loss…and discover the ultimate irony of Antietam’s bloody Cornfield.

By David A. Welker

Ezra Eugenius Stickley was born on 30 August 1839 near Strasburg, Virginia and, unlike many boys in his community, enjoyed full-time school at the Winchester Academy. Ezra continued his education at Bethany College, near Wheeling (West) Virginia until the outbreak of Civil War interrupted his studies. Although the Wheeling area was generally pro-Union, Ezra’s family and home community in the Shenandoah Valley was decidedly not, so on 5 July 1861 he returned to Winchester and enlisted in the Marion Rifles, which soon became Company A of the 5th Virginia Infantry. [1]

Ezra Eugenius Stickley was born on 30 August 1839 near Strasburg, Virginia and, unlike many boys in his community, enjoyed full-time school at the Winchester Academy. Ezra continued his education at Bethany College, near Wheeling (West) Virginia until the outbreak of Civil War interrupted his studies. Although the Wheeling area was generally pro-Union, Ezra’s family and home community in the Shenandoah Valley was decidedly not, so on 5 July 1861 he returned to Winchester and enlisted in the Marion Rifles, which soon became Company A of the 5th Virginia Infantry. [1]

The regiment Ezra found himself a part of was organized on 7 May 1861 by Colonel Kenton Harper. Augusta County provided eight of the 5th’s companies (C. D, E, F, G, H, I, and L), while Frederick County supplied two—Ezra’s Company A and Company K—and Rockbridge County raised Company B. Armed with muskets captured from the former Federal Armory at Harpers Ferry, the 5th Virginia was assigned to the First brigade—soon to be famous as the “Stonewall Brigade”—along with the 2nd, 4th, 27th, and 33rd Virginia and the Rockbridge Artillery and mustered into Confederate service on 8 June. [2]

Although Ezra Stickley and the 5th Virginia first “saw the elephant” on 1 July 1861 at a skirmish that became known as the Battle of Hoke’s Run (or Falling Waters), it was the First Battle of Manassas that established the hard fighting reputation of the brigade and its commander, General Thomas J. Jackson. The excitement of their first great battle not only didn’t end the war, but life settled into a toilsome, boring routine as the Southern Army remained glued to its fortified camp near Centreville, Virginia. The only notable experiences from this time occurred on 1 August when the 5th Virginia moved to a new campsite—abandoning its previous post so unhealthy the men dubbed it “Camp Maggot”—and on 11 September, when Colonel Harper resigned in anger after the irascible Stonewall Jackson refused him leave to return home to attend his dying wife. [3]

On 7 November, 1861 the 5th left Northern Virginia on a train headed to the Shenandoah Valley, where it joined newly-promoted Major General Jackson and the Stonewall Brigade, now led by Brigadier General Richard B. Garnett. Ezra was promoted to the rank of corporal and in this role joined the regiment in the Romney Campaign—a mostly forlorn series of marches—after which Ezra and the 5th Virginia briefly parted ways. [4]

By 12 February 1862, Ezra Stickley found himself detailed to the telegraph office in Winchester, Virginia, while the 5th Virginia marched off to participate in the Battle of Kernstown on 23 March. It remains unclear what precipitated Ezra’s time in the telegraph office or his return to the regiment, but by 29 April he was back in the ranks – and had been reduced once again to the rank of private. [5]

Private Stickley rejoined the 5th Virginia just as it and the Stonewall Brigade entered upon a dizzying string of campaigns and battles. First up was Jackson’s highly successful Valley Campaign and Ezra found himself engaged in the Battles of McDowell, Front Royal, First Winchester, and Port Republic. Barely had the men of the 5th Virginia and the Stonewall Brigade recovered from this campaign before they found themselves marching to the Confederate capital at Richmond, arriving in time to participate in the Seven Days Battle, fighting in the desperate conflicts at Gaines’ Mill and Malvern Hill. By August the 5th Virginia was once again on the move, this time chasing Union Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia, which the brigade first found at the Battle of Cedar Mountain. Returning to Manassas, the 5th Virginia settled into an unfinished railroad cut for the Second Battle of Manassas, during which brigade commander Colonel Baylor was killed and replaced by the 27th Virginia’s Colonel Arnold Grigsby. Under Colonel Grigsby, the brigade remained in reserve at the stormy Battle of Chantilly and during the march into Maryland. Taking part in the capture of Harpers Ferry, the 5th Virginia and its brigade had seen a series of tough battles, which nearly all had resulted in Confederate victory and which had led them for the first time into the enemy’s territory.

Sometime during all this marching and fighting Ezra Stickley was taken from the ranks and made one of the Stonewall Brigade’s orderlies (although he somewhat grandly referred to the job as being “an acting aide-de-camp”). Orderlies were soldiers selected to serve as messengers and perform other routine duties as directed by senior officers and although as with Ezra’s other assigned duties, it remains unclear why he was picked for this role. As an orderly, Private Stickley was mounted on a horse and—according to one account—issued a sword, field glasses, and other trappings of infantry officers highly unusual for simple privates. Regardless, it was an elevation that was soon to have a profound impact on Ezra’s life. [6]

When the Stonewall Brigade left Harpers Ferry, joining Jackson’s Command marching to unite with Lee’s forces at Sharpsburg, Ezra Stickley rode along with Colonel Grigsby and his staff. Pausing at a Sharpsburg house for water and to steal some tomatoes, Ezra admitted later that another reason for stopping was a presentment of his own death in the coming battle. Still, mustering up all his courage Ezra soon rode on join the brigade, which had moved into a woodlot north of town soon to be famous as the West Woods. Here the 5th Virginia would remain until morning brought an opening to the battle in earnest. [7]

The night that brought into being the single bloodiest day in American history was hardly one that anyone would chose as their last on earth. Drizzling precipitation that started around 9:00 on the 16th built into a solid rain by midnight. General Hooker called the night “dark and drizzly,” capturing what many of the men must have felt. Despite the weather and the pall of impending fight that hung over the fields around Sharpsburg, many of the soldiers slept unusually well. Newly-minted Corporal Austin Stearns of the 13th Massachusetts’ Company K recalled “I was tired, and sitting down soon lay down, falling asleep immediately; the last thing I remember was some horses of a neighboring battery stamping and their shoes striking fire on the rocks. The skirmishers were busy all night, so twas said, but I did not hear them, and as there was no alarm given I slept soundly till morning…” Sergeant Charles Broomhall of the 124th Pennsylvania—who like others in his regiment was about to experience his first battle—wrote “We lay down about 11 o’clock for the night along with thousands of others who were unconsciously taking their last earthy repose. Sorrowful to contemplate it.” A veteran in the 35th New York from Patrick’s brigade wrote home complaining more matter-of-factly that “… throwing out pickets we lay there until morning, not resting, however, on account of the alarms during the night.” [8]

Across the Hagerstown Pike, Confederate troops spent a restless night of anticipation. One man in Hood’s 4th Texas recalled “Here we lay down on the ground and let the shells fly over us, looking like balls of fire in the heavens. I don’t know how long this lasted, for I went to sleep…” Like his men, General Lee spent a restless night and by 4:00 a.m. was up directing Sandie Pendelton to bring up all the artillery not guarding the crossing to Virginia. One of Ezra’s commanders, the 5th Virginia’s Major Hazel Williams, wrote of the artillery firing that night “The display was grand, and comparatively harmless, except to the stragglers in the far rear.” [9]

Col. Grigsby

About 11:00 that night Colonel Grigsby directed his orderlies to rest, so Ezra and fellow orderly Private Cox each found a rock for a pillow and laid one of the pair’s blankets atop the rough bed. Stickley then placed his pair of new buckskin gloves on his “pillow,” presumably to soften it a bit, before placing over them the pair’s remaining blanket. With their horses’ reins tied to their feet—to restrain their mounts and be quickly in the saddle when needed—the pair drifted off to sleep in their rough bivouac. [10]

Seeing that dawn was nigh, Colonel Grigsby directed Stickley and Cox to ride the Stonewall Brigade’s lines and ensure the men put fresh caps on their muskets. Amidst performing this task and despite the coming battle, Ezra felt an overwhelming, nagging sense of loss about his missing right glove. [11]

Gloves of the type Ezra might have worn

As the sun rose, the Union began preparations for its attack. General Joseph Hooker’s plan was to send two of his three division’s forward through Miller’s Cornfield—while the third would hit Southern defenders south of the field in flank—aiming to unite and strike the main Confederate force at the small, white Dunker Church – the very spot the Stonewall Brigade was guarding. To soften and distract the Confederates ahead of the infantry assault, Hooker directed his artillery to fire into the rough area of the Southern line, in and astride the West Woods.

Union artillery shells began pouring indiscriminately into the West Woods. Ezra recalled years later what happened at that moment. “I was in the act of mounting my horse, a fine animal I had captured at Harpers Ferry. The first shell fell one hundred and fifty yards behind our line. The second fell about seventy-five yards in the rear of our line, doing no damage.” But Ezra’s luck was about to run out. [12]

“The third struck and killed my horse and, bursting, blew him to pieces, knocked me down, of course, and tore off my right arm, except for enough flesh to hold its weight. I saw my horse was about to fall on me where I lay. I jumped up and went straight to the brigade line of battle, and was caught by two of our men and thus prevented from falling. I was saturated with blood, on my right side from the blood of my own person and the left from the blood of my horse.” [13]

At that same moment, Colonel Grigsby ordered the Stonewall Brigade forward toward the Hagerstown Road to meet the advancing Union infantry threat. These were the Midwesterners of General John Gibbon’s Iron Brigade, one of Hooker’s three-pronged opening attack. They’d advanced down the road to threaten the left flank of Grigsby’s position, when unexpectedly more Yankees appeared from within the Cornfield across the road. Now Grigsby’s brigade, along with their counterparts in Jones’ brigade, were caught in a pincer attack. The Stonewall boys—and particularly the 5th Virginia—were taking tremendous casualties from the Union infantry and artillery fire. Knowing they couldn’t hold this spot long, Colonel Grigsby sent an aide rearward for reinforcements. Barely had division commander General Starke sent Talliaferro’s brigade forward, when Grigsby’s shattered brigade collapsed and ran for the rear. Their duty had been more than performed and now others would have to continue the fight for control of Miller’s Cornfield and the West Woods. [14]

Fighting in the West Woods

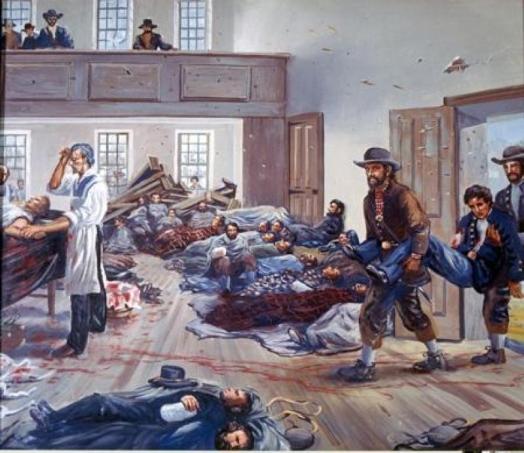

Ezra Stickley, however, was now fighting a very personal battle, one for his very survival. Colonel Grigsby detailed two men—who probably needed little persuasion to leave the maelstrom of the West Woods just then—to help him find medical care. “We started down east along the battle line,” Ezra wrote later, “They first put me on a horse to ride, holding me on. I became so very sick from the wounds that I had to be taken off. Not only was my arm gone, but there was a severe wound on my right side, much flesh torn off, rib broken and lung bruised. I then walked along, supported by the men, until we came to a furnished house on the field of battle”—perhaps this was Alfred Poffenberger’s place, which stood immediately behind and slightly south of Jackson’s line—“which had just been vacated.

“I was laid on the floor of the parlor, and two of our army surgeons came into the room where I was and began tying up my arteries to stop the blood, which possibly saved my life. But before they got through several shells struck the house and they left me alone and went their way.”

“Then a loitering soldier, dodging the battle, came to the door. He knew me and asked what he could do for me. I told him to get me water, water, water. He could find none and took me along down toward the field hospital at Sharpsburg. On the way we met our brigade ambulance train, in charge of Captain Burdette, of Staunton, Va., who soon saw me coming. He dashed up to me in great haste and called out: “Great God, Stickley, is that you?” He dismounted and came up to me, and I fell into his arms and knew no more until I awoke in the hospital yard on the ground among the thousands of shrieking, groaning, and dying soldiers.”

“After being roused up and regaining consciousness, I was ministered unto by my good friend Riddlemoser, our brigade medicine dispenser of Staunton, and by 3 P.M., reaction was brought about by stimulants. I was carried to the operating table, and our brigade surgeons Drs. Sawyer and Black…did efficient work and probably saved my life.” [15]

The war was over for Ezra Stickley, but not for his fellow soldiers in the 5th Virginia. The 5th retreated south from Antietam to participate in the Confederate victories at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, before marching north once again as part of General Lee’s second invasion of the North. At Gettysburg, the 5th Virginia and the Stonewall Brigade was on the far left of the Southern line, supporting Steuart’s brigade in its ultimately failed assaults on Culp’s Hill on 2 and 3 July, 1863. The regiment joined the Stonewall Brigade in the “Great Snowball Fight” on 23 March 1864, before moving deeper into Virginia that spring in an effort to thwart Grant’s Overland Campaign. Enduring heavy fighting at both the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, the 5th and its brigade was held in reserve during the fights at North Anna and Cold Harbor. Returning to the Shenandoah Valley following the Battle of Monocacy on 9 July, the 5th suffered high casualties at Third Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and Cedar Creek before rejoining Lee’s main army in the Petersburg defenses in December. When the 5th Virginia surrendered with the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia on 9 April, 1965, only 8 officers and 48 men—commanded by a single captain—remained.

Although the 5th Virginia continued carrying him on their regimental returns, Ezra Stickley had for months been at the C.S.A. General Hospital in Charlottesville, Virginia, where he remained until “retiring” from Confederate service on 4 November 1864. That fall—probably while still technically in the army—Ezra enrolled in the Washington College (today’s Washington and Lee University) law school, before transferring to study law at the University of Virginia. Graduating in 1866, Ezra Stickley opened a law practice in Woodstock, Virginia and was a prosperous, influential lawyer. [16]

“Stickley Hall,” which Ezra built in Woodstock, Virginia in 1868. The house still exists, as a private residence and office. Ezra stands at center, beneath the post. [17]

Curiously, sometime late in life the former private and successful lawyer found himself “promoted” to the rank of colonel. Published Virginia Bar Association minutes record the motions and comments of “Col. E. Stickley” and he even bears the rank on his tombstone, although the origin of this title remains unclear. Perhaps it’s an embellishment to make his wartime story match the success of his postwar life, as he might have done in the Confederate Veteran articles when describing his position at Antietam as “acting aide-de-camp” rather than the less glamorous—but accurate—“orderly.” Stickley’s Baltimore “Sun” obituary from 12 November 1915 claimed he had “served on the staff of General Stonewall Jackson during the Civil War” – which, as an orderly to the Stonewall Brigade’s commander he had been, but only in the most generous, stretched definition of “serving on a staff.” Perhaps it was an honorific title bestowed by friends and neighbors reflecting Ezra’s standing in the community, much as “Colonel” Sanders of chicken fame used the title during his life. [18]

Curiously, sometime late in life the former private and successful lawyer found himself “promoted” to the rank of colonel. Published Virginia Bar Association minutes record the motions and comments of “Col. E. Stickley” and he even bears the rank on his tombstone, although the origin of this title remains unclear. Perhaps it’s an embellishment to make his wartime story match the success of his postwar life, as he might have done in the Confederate Veteran articles when describing his position at Antietam as “acting aide-de-camp” rather than the less glamorous—but accurate—“orderly.” Stickley’s Baltimore “Sun” obituary from 12 November 1915 claimed he had “served on the staff of General Stonewall Jackson during the Civil War” – which, as an orderly to the Stonewall Brigade’s commander he had been, but only in the most generous, stretched definition of “serving on a staff.” Perhaps it was an honorific title bestowed by friends and neighbors reflecting Ezra’s standing in the community, much as “Colonel” Sanders of chicken fame used the title during his life. [18]

Ezra passed away on 11 November 1915, after unexpectedly suffering a relapse after surgery. Active in his local church throughout life, Ezra married twice after the war; first to Sophie Helm from Loudon County, Virginia and, after her 1882 death, to Mary Cutler from Louisa, Virginia. Ezra fathered eight children, a son and daughter with Sophie and six sons with Mary, who survived Ezra and lived until 1940. [19]

Ezra Stickley never recorded if he saw any irony in the fact that he’d started 17 September 1862 troubled by the loss of a new right glove and, by nightfall, had lost his right arm as well. Such oddities of war were all too common that warm September day, when surviving to see another sunrise itself had become the ultimate irony of Antietam’s Cornfield.

Endnotes:

[1] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXV, pp. 400-401.

[2] http://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/virginia/5th-virginia-infantry-regiment/.

[3] http://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/virginia/5th-virginia-infantry-regiment/.

[4] http://civilwarintheeast.com/confederate-regiments/virginia/5th-virginia-infantry-regiment/.

[5] https://www.fold3.com.

[6] Despite this title, Stickley appears to have acted not an aide-de-camp, in the conventional sense of that office, but rather as an orderly. Aides-de-camp were usually commissioned officers who not only carried orders but often issued their own orders in line with the senior officer’s plans and intentions, acting in his stead to make adjustments during battle. Because Ezra Stickley was a private–unlikely to have had the authority to do much more than pass along Colonel Grigsby’s orders–most likely he was an orderly.

[7] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXII, pp. 66-67. Vol. XXV, pp. 400-401.

[8] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. Series 1, Volume XIX, Pt. 1, p. 218 (Hereafter “OR”) ; Austin C. Sterns and Arthur A. Kent, ed., Three Years with Company K (London: Associated University Press, 1976), p. 125; Joseph L. Harsh, Sounding the Shallows: Confederate Companion for the Maryland Campaign of 1862 (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2000), p. 19; History of Lost and Found: Diary of CDM Broomhall, 124th Pennsylvania, http://aotw.org/exhibit.php, Entry for September 16th, 1862; R. L. Murray New Yorkers in the Civil War: A Historic Journey, Vol. 4 (Wolcott, N.Y.: Benedum Books, 2004). p. 76.

[9] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 610; Lee A. Wallace, Jr. 5th Virginia Infantry (Lynchburg: Virginia, H. E. Howard, Inc., 1988), pp. 41-42; “Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXII (December, 1914), p. 555.

[10] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXII, pp. 66-67. Vol. XXV, pp. 400-401.

[11] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXII, pp. 66-67. Vol. XXV, pp. 400-401.

[12] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXII, pp. 66-67. Vol. XXV, pp. 400-401.

[13] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXII, pp. 66-67. Vol. XXV, pp. 400-401.

[14] Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, (California: Savas Beatie, 2012), p. 65, p. 77.

[15] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXII, p. 66-67.

[16] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXV, pp. 400-401; https://www.fold3.com; “The Sun,” Baltimore, Maryland, November 12, 1915, Volume CLVII, Issue 155, P. 3.

[17] Jean M. Marsh, Shenandoah County Historical Society, Images of America – Shenandoah County (Charleston, SC, Arcadia Publishing Co., 2010), p. 34.

[18] “The Sun,” Baltimore, Maryland, November 12, 1915, Volume CLVII, Issue 155, P. 3.

[19] “The Confederate Veteran,” Vol. XXV, pp. 400-401; https://www.fold3.com; https://Ancestry.com.

Very nice post on Stickly. Just a heads up, the photo is not Grigsby. It is Bradley T. Johnson who was from Frederick, MD. Johnson was with the army when they moved into Frederick as the provost marshal, but for some unknown reason was not at the battle of Antietam.

LikeLike

Thanks! And good catch on the picture, which I’ll fix.

LikeLike