John Cook swung his bugle over his shoulder and wrested from the dead man his leather pouch, bearing the undelivered shell without which the cannon was useless. From that moment on, John Cook worked a gun alongside the trained artillerymen to face down the onslaught of Wofford’s attacking Texas Brigade. It was an act that earned John Cook—who had turned fifteen years old barely a month before—the Medal of Honor.

By David A. Welker

John Cook was born in Cincinnati, Ohio on 16 August 1847, probably the oldest of Thomas and

Bugler John C

Lydia Cook’s children. Little is known of John’s probably-modest family or his early years, but in all likelihood his childhood differed little from other boys growing up in western Ohio in mid-Nineteenth Century America. All that would change on 7 July 1861, however, when at age 13 John Cook enlisted at Cincinnati to become a bugler in the Union Army, assigned to Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery. And as strange as it may seem to modern Americans, John’s parents had authorized his joining the army by signing or verbally giving their approval. [1]

Like other young boys enlisted by both Union and Confederate armies, John Cook’s role in the army was to serve as a “musical message service,” using the bugle’s high-pitched reach to broadcast officers’ orders beyond the range of their human voices. Spreading these orders was a central part of army life, reaching from the humdrum routine of daily camp life, through the organized chaos of the march, to the excitement and terror-filled confusion of battle. It was in the latter role that a boy’s bugle call could spell the difference between keeping the human military machine of the army working together or its breaking down in the confusing fog of war. To perform this role, John Cook and the other boys spent their early days in the army learning to play their instrument—few came to the service with these skills—and memorizing the dozens of calls they would soon be called upon to issue in an instant.

John left Ohio—probably for the first time in his life—in October 1861 headed to

Capt. Joseph Campbell

Washington to join the 4th US Artillery’s Battery B, which arrived there from its former peacetime post in Utah Territory. Once in Washington, the battery received a new commander—1861 West Point graduate Captain Joseph B. Campbell replaced newly-minted Brigadier General John Gibbon, just appointed Chief of Artillery in McDowell’s I Corps—and deployed in the capital’s defenses. In April 1862 Battery B moved to the Falmouth, Virginia area as part of the force protecting the capital while McClellan’s Army of the Potomac futilely advanced on Richmond. The young bugler and his battery experienced their first combat of the war on 9 August 1862 at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, before participating in the much larger Second Battle of Manassas on 28-30 August 1862.

After a few days of much needed rest John Cook and the battery departed on 6 September 1862, chasing Lee and his Confederate Army into Maryland. Only peripherally engaged in the Battle of South Mountain, Captain Campbell and his 4th US Artillery joined the rest of McClellan’s Union Army in moving west until it finally found Lee’s army on the banks of Antietam Creek. Crossing the span on the evening of 16 September, John Cook and the battery spent a restless night on the Joseph Poffenberger farm, with only the North Woods between them and the nearby Rebel host.

Well before dawn an artillery duel opened, in which the 4th US Battery B took an active part after deploying forward “about 75 yards distant from and to the left of the [Hagerstown] turnpike…” Although most Union guns were blindly shelling the Confederates in the West Woods, Battery B had been sent forward to support Gibbon’s impending attack. Gibbon’s Iron Brigade had been selected by General Hooker—architect of McClellan’s opening attack at Antietam—to comprise the right-most of his three-pronged attack on Jackson’s Command at the Dunker Church. [2]

Gibbon’s advance had gotten off to an excellent start but had stalled after only 10 minutes when the 6th Wisconsin had become bogged down in an increasingly desperate firefight against a much larger force to its right, which would turn out to be two brigades of fresh Confederate infantry. To break this stalemate, Gibbon ordered the 19th Indiana and the 7th Wisconsin across the Hagerstown Pike and southwestward toward the left flank of the two enemy brigades holding his line in check. Moments later, Gibbon ordered the 2nd Wisconsin forward on the left to further help the beleaguered 6th Wisconsin. To support his advancing infantry, Gibbon called forward a two-gun section from Campbell’s battery commanded by Lieutenant James Stewart and posted it in the center of his expanding line. Gibbon’s adaptation had the right of his brigade striking the left flank of these two defending Southern units—Jones’ and Grigsby’s brigades—while the left half hit them in front and on the right. If this pincer movement worked, they would soon enough reunite and resume the drive to the Dunker Church. [3]

Lieutenant Stewart quickly ordered his two guns forward up the Hagerstown Pike at a

Lt. James Stewart

run. Upon reaching their objective, Stewart led them to the right of the road and into D.R. Miller’s barnyard, still flush with stacks of harvested hay. Posting his two guns facing south and directing them to open fire in support of the Wisconsin men, Stewart ordered his caissons moved back toward the barn to keep them safe from the increasingly deadly Rebel gunfire. Standing firm amidst this exposed forward position, too, was the battery’s young bugler, who had been detailed to support Stewart’s section. [4]

Meanwhile, well to the left of Gibbon’s command, Hood’s Confederate division had

Co. William Wofford

crossed the Hagerstown Pike and deployed for battle. While Law’s brigade deployed on Hood’s right, near the East Woods, Wofford’s Texas Brigade held Hood’s left and at once advanced toward Gibbon’s men. Wofford pushed his Texans up the long slope of the shattered Cornfield, maintaining order and dress despite having been so quickly thrown into this fight. They pushed the Yanks back 600 or so yards when the left of Wofford’s line—the Hampton Legion and the 18th Georgia—suddenly stopped altogether, though they continued firing rapidly. What had halted the two regiments were two Union artillery pieces deployed on a rise across the Hagerstown Pike, pouring a deadly, accurate fire of canister into the flank of Wofford’s line. And like the experienced officers there were, the Hampton Legion’s Lieutenant Colonel Gary and the 18th Georgia’s Lieutenant Colonel Ruff moved their regiments’ front to the left to return fire on this threat. [5]

What they faced here was not only Lieutenant Stewart’s two-gun section of the 4th US artillery but their infantry support, the 80th New York, as well. The Union men probably couldn’t appreciate it at that moment, but opening an unexpected fire on Wofford’s flank had stripped the Southern brigade’s momentum and stopped the Confederate attack to retake the Cornfield nearly in an instant. Until those Yankee guns were silenced, Hood’s advance was at risk. For the men of the 18th Georgia and the Hampton Legion, though, silencing the guns was more an act of simple survival than tactical maneuvering. Lieutenant Colonel Ruff knew in an instant that the best way to get rid of the guns was to attack their weakest point – the men crewing them. Ruff instantly ordered some of his best shots out of the ranks and across the road to open a sniper fire on Stewart’s 4th US gunners. Within a few minutes, their deadly work was beginning to take a toll on Stewart’s gun crews. [6]

As the sniping fire of the 18th Georgia’s skirmishers exacted an increasingly high human toll from the 4th US artillery, Lieutenant Stewart was doing his level best to recrew his guns. After losing his mount to the 18th Georgia’s fire, Stewart raced to the rear on foot and gathered any man available to serve as a gunner. [7]

As Stewart was ordering his new gunners into their roles, he glanced to the rear and beheld a welcome sight. Captain Campbell and the rest of the 4th US battery B was racing down the turnpike toward their position. Deploying immediately on the left of Stewart’s section, the remaining four guns were almost at once adding firepower to Stewart’s hold on this vital position. Though it might not have occurred to Campbell at the time, the presence of these fresh guns and crews also gave the 18th Georgia’s riflemen new targets at which to aim, increasing the threat of instant death that had until recently been focused on Stewart’s men alone. [8]

With his guns deploying, Captain Joseph Campbell dismounted. At that same moment, John Cook—his detached duty completed—reported to the new senior officer on the field. But even before he could acknowledge the boy’s presence, a volley tore into Joe Campbell’s shoulder and his horse, killing the poor animal and wounding the battery’s commander. Instinctively, John Cook grabbed his wounded commander and helped him to the rear.

The two soldiers made it as far as D.R. Miller’s haystacks, which had become a makeshift haven for the 4th US artillery’s wounded. “The two straw stacks offered some kind of shelter for our wounded” recalled John Cook years later, “and it was a sickening sight to see those poor, maimed, and crippled fellows, crowding on top of one another…” John Cook made sure his commander got the care his rank suggested he deserved and placed Captain Campbell not amidst the crowd behind the haystacks, but in the care of a driver. But John Cook’s work wasn’t done yet.

Before parting, Captain Campbell ordered John to pass word to Lieutenant Stewart that he now had command of the battery. John, without hesitation, returned to the battery’s exposed position to relay this message. But completing even this dangerous task didn’t end the boy’s work. The battery was running thin on manpower, even with the new guns in place, and John noticed a man from one of the gun’s crews lying dead with a full ammunition pouch still wrapped around his shoulders. Knowing this meant that one of the guns was unable to fire and at risk, John swung his bugle over his shoulder and wrested the leather pouch from the dead man. From that moment until Campbell’s battery was moved to the rear, John Cook worked a gun alongside the adults. It was an act that would earn John Cook—who had turned 15 years old a month before—the Medal of Honor. [9]

An artillery haversack of the kind John Cook used

The Georgians’ deadly accurate fire was doing to the crews of Campbell’s other four guns what it had already wrought on Lieutenant Stewart’s section. Later returns would show that the battery had lost 38 men and 27 horses. Losing so many men and horses put the battery at risk of being overrun and losing its position and guns to the enemy. General Gibbon, watching all this not far away, knew all this well enough but his concern was personal. After all, this was his old battery which the general referred to in reports not by its then-name of “Campbell’s battery” or by its formal, military title of “the 4th US artillery, battery B” but instead as “Gibbon’s battery.” In his mind that’s what it was and would always be and at that moment, Gibbon’s battery was dying. [10]

Gen. John Gibbon

Seeing the captain of the left-most gun fall—leaving it without anyone to command, aim, or fire the brass Napoleon—Gibbon sprang without thinking to the piece. Ordering the remaining crew to load a double round of canister, Gibbon aimed the piece and fired into the face of the 18th Georgia and the Hampton Legion, which were trying desperately to advance on the guns. Again and again, General Gibbon ordered the crew to load and fire their huge shotguns into the advancing enemy. So close were the Rebels that the battery’s rounds were tearing up the ground and blasting the post-and–rail fence bordering the Hagerstown Pike into splinters.

John Gibbon knew this stalemate couldn’t go on for long and decided to act. Seeing a body of troops reorganizing in the swale on the northern end of the Cornfield, just across the road, Gibbon intended to turn them into infantry support for his battery. Racing across the road, Gibbon found Major Rufus Dawes and instantly directed “Here, major, move your men over, we must save those guns!” His face streaked with gunpowder and sweat, the general pointed to the rear of his battery’s position before returning there. With that, Rufus Dawes ordered his now-ragged command containing the remains of the 2nd and 6th Wisconsin to “Right face, forward march!” and the line surged across the road to take position on the right of the 80th New York. Gibbon’s guns had just received some much-needed help and were soon moved to the rear to lick their wounds. Even so, John Cook and the 4th US Battery B wasn’t done yet. [11]

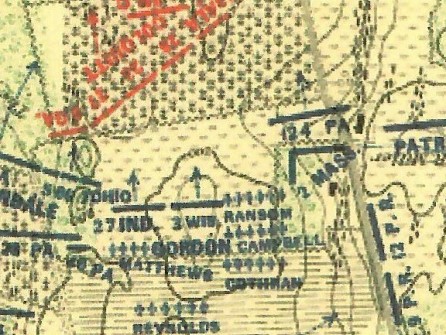

John Cook and the battery were once again pushed forward, this time around midday, to support Gordon’s brigade of Mansfield’s XII Corps. Joining Ransom’s 5th US artillery battery C, Lieutenant Stewart brought Campbell’s battery back onto the field, deploying in almost the same spot in the plowed field below the North Woods from which the battery had supported Gibbon’s earlier attack at dawn. However, General Gibbon had ordered them here apparently unaware that Gordon’s 3rd Wisconsin was deployed nearly in front of the battery’s new post, leaving Stewart’s artillerymen as little more than targets for Rebel fire. The lieutenant instantly ordered his guns loaded with canister then, sending the limbers and horses to the rear, Stewart had his men to lie down between the guns, using the slight rise of the ground as a natural entrenchment. For now they would wait. [12]

support Gordon’s brigade of Mansfield’s XII Corps. Joining Ransom’s 5th US artillery battery C, Lieutenant Stewart brought Campbell’s battery back onto the field, deploying in almost the same spot in the plowed field below the North Woods from which the battery had supported Gibbon’s earlier attack at dawn. However, General Gibbon had ordered them here apparently unaware that Gordon’s 3rd Wisconsin was deployed nearly in front of the battery’s new post, leaving Stewart’s artillerymen as little more than targets for Rebel fire. The lieutenant instantly ordered his guns loaded with canister then, sending the limbers and horses to the rear, Stewart had his men to lie down between the guns, using the slight rise of the ground as a natural entrenchment. For now they would wait. [12]

While John Cook and his fellow 4th US men hugged the ground for dear life, much occurred in the battle. General Hooker was wounded and replaced by Major General Edwin Sumner as he brought his II Corps into the fight. Sumner led Sedgwick’s division into battle, nearly taking the West Woods and breaking Lee’s line at the Dunker Church. But just when victory seemed within grasp, McLaws’ Southern troops appeared to turn the tide of battle once again against the Union. Sumner’s men fled the West Woods in droves, leaving the Union left in danger of collapsing completely. [13]

But once again, just as things seemed blackest, the Union artillery—including the 4th US Artillery, battery B—opened fire from the Cornfield and saved the day, halting McLaws’ attacking line. General Gibbon had posted battery B on the edge of D.R. Miller’s orchard—or what was left of it—on the left of Reynolds’ battery along the ridge north of the Cornfield. When enemy infantry appeared in the road, Stewart now had fresh targets. “I ordered my guns to be loaded,” recorded the lieutenant, “The enemy commenced to fall back on the same road, I waited until I saw four stands of the enemy’s colors directly in front of my section, and then commenced firing with canister, which scattered the enemy in every direction.” Amidst all this carnage, 15 year-old bugler John Cook remained firm, providing the battery with communications and a fresh man to work a gun when needed. [14]

John Cook was with the battery when it participated in the Battles of Fredericksburg,

The 4th US Arty, Bty B’s Gettysburg monument

Chancellorsville, and at Gettysburg. There John Cook once again distinguished himself in battle by carrying messages through intense enemy fire over a half-mile of contested ground and helped destroy one of the battery’s damaged caissons to prevent it being used by the enemy. During his service the young bugler had seen 33 battle actions and had been wounded more than once.

On 7 June 1864, at age 16, John Cook mustered out of Federal service in Philadelphia upon the expiration of his term and returned to his home in Cincinnati. On 30 April 1870 John Cook married Isabella MacBryde, a 16 year old immigrant from Scotland. Together they would have three children—Margarette, born in 1871; John Jr., born in 1873; Rebecca, born in 1876—and lived in the Cincinnati area, where John worked a variety of manual labor jobs including by 1880 work in a local shoe factory. Sometime after 1880, though, the Cook family moved to Washington, DC, where John had secured steady employment at a watchman with the Government Printing Office.

John was honored for his unusual war service on 30 June 1894 when he was presented with the nation’s highest award, the Medal of Honor. The citation read in part “The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Bugler John Cook, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 17 September 1862, while serving with Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, in action at Antietam, Maryland. Bugler Cook volunteered at the age of 15 years to act as a cannoneer, and as such volunteer served a gun under a terrific fire of the enemy.” [15]

John Cook’s life ended on 3 August 1915 in Washington, DC. Isabella joined him in eternity less than a year later, on 16 March 1916 and they are buried together in Section 17 of Arlington Nation Cemetery. [16]

Although John Cook’s military service had comprised only a very few years of his long life, it had been a—and perhaps, the—defining moment of his time on earth. John Cook had entered the battle for Antietam’s Cornfield as a barely 15 year old boy; he’d emerged from its horror as the equal of any other man in the Union’s honored ranks.

Endnotes:

[1] “US Army Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914” US Archives, Washington, DC.; 1860 and 1870 United States Federal Census.

[2] United States War Department. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), Series 1, Volume XIX, Pt. 1, p. 229.

[3] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 248; Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, p. 222; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 72-76; Gaff On Many a Bloody Field: Four Years in the Iron Brigade (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), p. 185. “US Army Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914.” US Archives, Washington, DC.

[4] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 229.

[5] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 928, p. 930.

[6] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 930.

[7] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 229.

[8] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 229.

[9] W. F. Beyer and O. F. Keydel, Eds. Deeds of Valor (Platinum Press, Detroit, 1903), pp. 75-76.

[10] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 248-249.

[11] Rufus Dawes A Full-Blown Yankee of the Iron Brigade: Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1962), pp. 91; OR, Vol. XIX, I, p. 249.

[12] Ezra A. Carman and Joseph Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign of 1862; Ezra A. Carman’s Definitive Study of the Union and Confederates at Antietam. (New York: Routledge Books, 2008), p. 240. Ezra A. Carman and Thomas G. Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II: Antietam (California: Savas Beatie, 2012), pp.126-130.

[13] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 230; Carman and Pierro, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, pp. 270-272; Carman and Clemens, Ed. The Maryland Campaign, Vol. II, pp. 219-223.

[14] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 230.

[15] http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=1711.

[16] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/13147/john-cook. Obituary: John Cook, Government Printing Office Employee Won Honor for Valor in the Civil War, The Washington Post, 1915-08-04, pg. 3.

I do not think John Cook is the son of Lydia and Thomas Cook. He would not have been 14 in June 1860 if his birthday id in August 1847. In subsequent Census 1880, 1900 and 1910 records indicate his father was born in New Jersey and his mother in England. Both Thomas & Lydia were born in England. There is something that does not add up in this scenario.

LikeLike

His 1847 birthdate seems secure; he was, however, 13 at the time of his enlistment–not 14, but close–so I’ve changed that. Hey, math was never my strong suit…

I believe that Thomas and Lydia are the most likely candidates for being his parents, based on available data. You’re certainly correct that in the 1910 Census John lists New Jersey and England as his parent’s birthplaces, but no one with “John Cook” as their child in the Cincinnati area in the 1850, 1860, or 1870 Census lists their birthplaces as New Jersey and England. It’s certainly possible that the census taker was mistaken on one or more forms, either in recording Thomas and Lydia’s birthplaces or John’s parents’ birthplaces. Perhaps John was mistaken about his parents origins or after the war was concealing that they hailed from Virginia and the defeated Confederacy. Perhaps John wasn’t living with his parents in Cincinnati in 1860 but rather with relatives bearing the same last name (which wouldn’t show up on a census form). And the census forms certainly contain their share of errors… Still, I’ve added “probably” to reflect the uncertainty.

LikeLike

There is another entry in the 1860 Census for Cincinnati that shows a household headed by Mary A Cook a seamstress born in England with children Emily, John, George, Ann and Ella. John is 12 years in June 1860 which would make him 13 in August 1860. The only thing out of place is the records indicate John was born in Kentucky and we assume John Cook was born in Ohio based on other available information.

LikeLike

Correction both Thomas and Lydia were born in Virginia

LikeLike

Cook enlisted on June 7, 1861 and was discharged June 7, 1864 at the expiration of his service in the field in Virginia.

LikeLike

John Gibbon was appointed Chief of Artillery for McDowell as a Captain. The senate would confirm his appointment as a Brigadier General of Volunteers on May 2, 1862.

LikeLike

True, but as I’ve written this it’s not incorrect. I crafted the sentence this way to tightly wrap together for the reader Gibbon’s connection to the battery, Campbell’s elevation to replace him, where Gibbon went next, and to introduce Gibbon as a general. Yes, this is lots to pack into a single sentence but otherwise it takes the reader deep into a tangential story about Gibbon and the battery. Remember, this piece is about John Cook and his link to the Cornfield, not a history of John Gibbon or Battery B (although both could be good stories on their own).

LikeLike

Battery B 4th U. S. Artillery was engaged in the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862 in support of Gibbon’s Brigade which advanced up the National Road toward Turner’s Gap and the awaiting Confederate forces.

LikeLike

Although the entire battery wasn’t involved at South Mountain, Stewart’s two-gun section was involved very late in the day as part of Gibbon’s drive against Colquitt’s brigade. I tweaked the text to reflect this limited involvement.

LikeLike