With the sun glistening off rainwater on the tall, waving cornstalks this clear September morning, David Miller could have no way of knowing that soon his cornfield would become the most dangerous place to be on earth.

By David A. Welker

Tuesday, September 2nd, 1862 dawned bright and clear on the rolling hills of western Maryland. David Miller was up early and working as usual around his small but prosperous farm. Miller—known to all by his initials, D. R.—had much to do this morning. His modest cattle herd would need to be led to the pastureland that made up much of the farm before turning to another of his many daily chores. David and Margaret Miller could feel grateful that their 200-acre farm had been providing the couple and their children a solid living for many years.

The Millers’ farm sat about one half mile north of the quiet hamlet of Sharpsburg,

- D. R. Miller’s farm toda

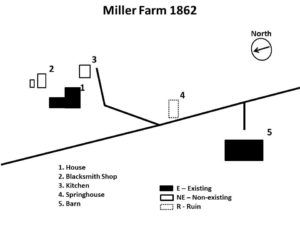

Maryland, straddling the Hagerstown Pike that ran north out of town. Across the Hagerstown Pike, the first sight that greeted D. R. each morning as he walked from the house was his sizable barn with its attached, single-story extension that served as a stable for the cattle and hogs. The acres he owned on the eastern side of the road this year had held the straw and hay that would sustain his herd through the winter. The difficult work of harvesting the hay was done and it now lay in huge stacks across the road from his house.

The small but comfortable two–story, whitewashed house sat facing west on the eastern edge of the Hagerstown Pike. Behind the house was a separate kitchen reflecting the home’s early 1800s origin—now replaced by a more modern in-house kitchen—and a small building serving as a blacksmith’s shop. To the left of the house along the road was a springhouse which provided the family’s water, located about halfway between the barn and the house. Behind the main house and two outbuildings stood an orchard from which Margaret Miller could put some treats on the table throughout the year. The nearby garden this year was planted in pumpkins, potatoes, and beans and much of its bounty was already in cans for the coming winter.

The bulk of D. R.’s land, though, lay on the eastern side of the road behind the farmstead. The northernmost field was plowed in an effort to turn the remains of its already-harvested crops into fertilizer by the time of spring planting. The next field to the south, directly behind the house, was a twenty-acre pasture for the cattle to graze in. Another pasture, this one nearly forty acres, stood on the southern end of Miller’s land and sloped down gently to border the Smoketown Road and the farm of the Mumma family. In the very center of D.R.’s property stood another twenty-acre field, situated on a small hill, this year planted with corn. [1]

The Miller house in 1862, immediately after the battle.

Surveying his cornfield, D. R. must have felt a mix of satisfaction and dread. This year’s corn crop was green and tall, bearing many thousands of nearly-ripe ears that would sustain his cattle through the winter and offer important variety in their diet. But before a single cow could chew any of the yellow grain, it would have to be harvested and stored in the barn. So backbreaking and difficult were such harvests that they were celebrated in many farming communities with a social gathering, often held more out of relief for a difficult task completed than in thanks for a generous bounty. It was a task so hated by some young men that they had fled their family farms to join the armies of the Union or the Confederacy just to avoid this annual burden. Seeing the morning sun glisten off the rainwater on the tall, waving cornstalks on this clear September morning could only have reminded D.R. that this long, difficult job lay before him in the coming weeks. David Miller, though, could have no way of knowing that in two weeks’ time his cornfield would become the most dangerous place to be on earth. [2]

D. R. Miller’s farm had once been part of a tract granted to Joseph Chapline called “Loss  and Gain,” which he bequeathed to his son, James Chapline, in the late 1790s. In 1796, James Chapline sold 40 acres to Jonas Hogmire, who bought another 40-acre lot from Chapline the following year. In 1799, Hogmire sold 81 3/8 acres to John Myers, who built the first house here. Originally a log structure, Myers later built a modern house—which still stands today—featuring several rooms served by a central chimney system, resting on a limestone foundation. An addition built on the north side included a dining room, kitchen and porch. In 1812, John Myers added another 150 acres and several smaller lots bought once again from Chapline. Before his death in 1836, John Myers had added a blacksmith shop (which may have been the original log house), an out-kitchen, a springhouse, and two gardens; across the road Myers had built the barn, a stable, a corn crib/wagon shed, and hog pens. [3]

and Gain,” which he bequeathed to his son, James Chapline, in the late 1790s. In 1796, James Chapline sold 40 acres to Jonas Hogmire, who bought another 40-acre lot from Chapline the following year. In 1799, Hogmire sold 81 3/8 acres to John Myers, who built the first house here. Originally a log structure, Myers later built a modern house—which still stands today—featuring several rooms served by a central chimney system, resting on a limestone foundation. An addition built on the north side included a dining room, kitchen and porch. In 1812, John Myers added another 150 acres and several smaller lots bought once again from Chapline. Before his death in 1836, John Myers had added a blacksmith shop (which may have been the original log house), an out-kitchen, a springhouse, and two gardens; across the road Myers had built the barn, a stable, a corn crib/wagon shed, and hog pens. [3]

David R. Miller purchased this farm for $53 per acre on April 24, 1844. The money, however, was almost certainly fronted by D. R.’s father, John Miller, because ownership of the land was transferred to him that same day. John Miller retained legal ownership of the farm until his death in 1882, even though it was D. R. who worked the land.

The Millers were already a prominent Sharpsburg family by the time they acquired this particular farm. D. R. was named to honor his grandfather, David Miller, who along with his wife, Catherine Flick, had emigrated from Germany in the 1760s. By 1768, the Millers had settled in the newly-established town where they opened Sharpsburg’s first store. David’s son, John, worked in the family store but also opened the town’s first post office, a hotel, and a gristmill, earning enough money to invest in several nearby farms. During the War of 1812, John was commissioned a colonel in the Maryland Militia and would ever after be known as Colonel Miller. Colonel Miller’s wealth enabled him to ensconce each of his sons on their own farm near Sharpsburg. [4]

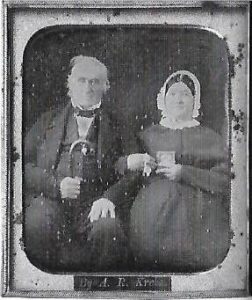

David and Margaret Miller well after the war

D. R. had lived on his farm for two years when on April 2, 1846, he married Margaret Pottenger. By 1862, David and Margaret had added four children (Mary, 10; Elnora, 8; James, 7; and Nettie, 4) to their family and worked hard to build their farm into a prosperous operation and their home to a happy place. On September 17, 1862, though, all of their dreams and hard work would be desperately threatened by a firestorm of human making. [5]

As Lee’s Confederate army began converging on Sharpsburg on September 15, D. R.

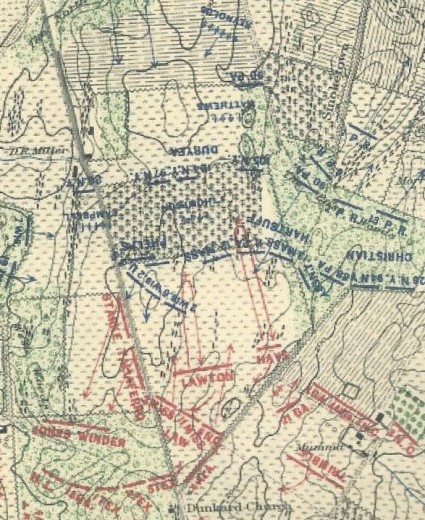

D. R.’s farm – including the Cornfield, as well as the North, East, and West Woods.

wisely drove his livestock away to safety, “all except one angry bull that refused to be herded”. Then, either late that day or early the next, D. R. and his family left their home for the relative safety of his father’s house on the other side of Houser’s Ridge, west of the ridge on which Confederate forces were increasingly deploying – a ridge that ran through the western end of his farm. If D. R. had any qualms about the decision to abandon his farm they must have been settled when Union forces began deploying on the eastern bank of nearby Antietam Creek.

As the fog began lifting around 9:00 a.m. on September 16, 1862, Confederate skirmishers nearest the Middle Bridge over Antietam Creek began shifting, creating uncertainty among the two Union batteries newly deployed to cover the bridge. As the Union gunners loosed the fury of their ten guns, driving off the skirmishers before turning on a larger infantry force—probably two brigades commanded by Nathan “Shanks” Evans—Confederate artillery of Squires, Bachman, and Riley’s Batteries opened in reply. Although for nearly 45 minutes the two lines of artillery dueled as the sun rose in the sky, eventually the weight of Union artillery firepower convinced General Longstreet to end the mismatched fight by ordering his batteries away. So ended what General D. H. Hill described as “the most melancholy farce of the war.” [6]

Union batteries nonetheless pressed on with their bombardment, raining fire down on Sharpsburg itself. For nearly half an hour, the Yankee guns tore at the town’s modest buildings and brought the town to life as if someone had stepped on an anthill. People raced from their homes, loading any available conveyance to get themselves and their belongings away from the two armies. Young William Houser recalled a shell blasting apart a fence line as his family raced past on their way out of town. The Grice family shoved some food and clothes into a case and, sitting as many of the children as possible on their horse, set off to join many of their neighbors in nearby Killiansburg Cave.

As shells began raining down on town and the Confederate lines, the Millers realized that in their excitement to leave the family parrot had remained behind in its cage. Racing back home, D. R. dashed to his porch, where the cage still hung from the porch roof by a leather strap. But before he could reach the cage a shell fragment severed the cord, sending the cage crashing to the ground and killing poor Polly in the process. D. R. raced back to his father’s home before the cost of this mission could prove to be greater than the life of a bird. [7]

The Miller family remained safely away when, late on Tuesday the 16th, Union forces crossed the creek and arrived on the northern and eastern edge of their farm. That night Union Major General Joseph Hooker rode the fields behind the Miller home, choosing to send his attacking I Corps at dawn to strike Confederate troops lining the Dunker Church ridge, assigning the modest white-washed church as its target. Hooker’s decision ensured that at least the opening of this fight would occur on the Miller’s property. Moving from the Miller’s northern woodlot—soon to be known as the North Woods—Union troops would drive toward the Dunker Church, which sat on the edge of the Miller’s western-most woodlot, which would become better known as the West Woods. To reach this point on the southwestern end of the Miller’s property, Union troops would march southward across the length of the Miller farm, though their two grassy fields which flanked a cornfield. The Miller’s once-peaceful farm was to be Joe Hooker’s battlefield and nowhere would the fighting be more intense and deadly than in their bountiful cornfield.

Stonewall Jackson had made the Miller’s cornfield matter by deploying an advanced line, consisting of the brigades of Generals Lawton and Hays, just south of the field to intercept any Union attackers heading toward the main Confederate line. General Hooker had unknowingly played right into Jackson’s hands by attacking southward through the Miller’s cornfield, right at Jackson’s position. For nearly five hours on Wednesday morning, September 17, Union and Confederate troops would battle to control the Miller’s cornfield. While this bloody, intense fighting ensured that the simple field became an American icon of death and suffering, it was D. R. Miller’s innocuous decision to plant this field in corn for the 1862 growing season that ensured these acres as would forever be known as “the Cornfield.”

consisting of the brigades of Generals Lawton and Hays, just south of the field to intercept any Union attackers heading toward the main Confederate line. General Hooker had unknowingly played right into Jackson’s hands by attacking southward through the Miller’s cornfield, right at Jackson’s position. For nearly five hours on Wednesday morning, September 17, Union and Confederate troops would battle to control the Miller’s cornfield. While this bloody, intense fighting ensured that the simple field became an American icon of death and suffering, it was D. R. Miller’s innocuous decision to plant this field in corn for the 1862 growing season that ensured these acres as would forever be known as “the Cornfield.”

The Cornfield and the nearby fights it spawned extracted a tremendous cost from both South and North. Of the 9,298 men Lee lost at Antietam, roughly 7,000 of those had fallen in fighting on the Union right in or around the Cornfield. McClellan, too, lost most of his men sacrificed at Antietam in fighting around the Cornfield, some 9,913 of his total 12,401 battle casualties. Both Lee and McClellan lost nearly two thirds of their armies in fighting around the Cornfield. D. R. Miller’s harvest of death had simply bled both armies dry.

Possibly the Miller family on their porch two days after the battle (possibly from l-r, Margaret, Mary, Nettie, Elnora, and James)

When the Miller family returned to their farm shortly after the battle ended—probably late on September 18 or on the 19th—they certainly must have been surprised to find their home largely intact. Although there was minor bullet and shell damage to the main house—surprisingly, many of the windows remained unbroken—only the old blacksmith’s shop had been destroyed (probably by artillery shelling, although the means of its destruction remains uncertain). Even the large barn had survived nearly unscathed.

Still, their crops had been destroyed and their home and farm buildings were still being used as makeshift hospitals. The greater part of the Cornfield’s stalks had been “cut as closely as could have been done with a knife,” as General Hooker famously recorded in his official report of the battle. Even the grassy and fallow fields had been plowed by hundreds of artillery shells, many of which remained unexploded, deadly threats that precluded plowing or cultivation. Their woodlots—the North, East, and West Woods—had been shattered by artillery fire and were littered with dead and wounded. The hay once stacked neatly by the barn, meant to sustain their horses and cattle though the winter, was in disarray and being used now as fodder for hundreds of Union mounts and artillery horses. [8]

D. R. Miller eventually filed a claim to the US Government for $1,237.75 in compensation for the damages. Not until July 6, 1872 would he receive payment on this claim, of $995. Until then, like the soldiers suffering throughout their farm, the Millers would have to make do.

D. R. Miller and his family continued working the farm for the next twenty years. The farm’s legal owner, D. R.’s father Colonel John Miller, died in 1882 leaving no will to divide his considerable land holdings among his eight children. A fierce legal battle ensued that resulted in a sell-off that allowed D. R. and Margret to finally buy the northern half of their farm, 150 acres that included the house and the farm buildings. The southern half, of fewer than 100 acres, was apparently sold to another buyer. Regardless, David and Margaret Miller finally owned the farm they’d worked and lived on for 40 years.

Barely three years later, though, the Millers retired from farming, in 1886, selling their

- David and Margaret Miller’s resting place

property to Euromus Hoffman on March 29 that year. Moving into a comfortable home in town, their retirement was unfortunately to be short-lived. Margaret passed away on November 13, 1888 at the age of 63, leaving David on his own. D.R. lived for five years until he too, passed away at 78 years of age on September 10, 1893. Margaret and David rest together for eternity in the Mountain View Cemetery in Sharpsburg. [9]

The Miller farm, and the famous “Cornfield,” remained a working farm until 1989 when it was purchased by the Conservation Fund, a non-profit organization which in 1990 donated it to the National Park Service. Today, you and I—and all Americans—own David and Margaret Miller’s farm. For over 40 years the Millers faithfully preserved their historic charge – now it’s our turn to protect Antietam’s Cornfield for future generations. [11]

Notes:

[1] Kathleen A. Ernst, Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1999), pp. 132-134.; Keven M. Walker, Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscapes (Sharpsburg, MD: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010), pp. 34-38.

[2] Walker, Antietam Farmsteads, pp. 34-38.

[3] Walker, Antietam Farmsteads, p. 38.

[4] Walker, Antietam Farmsteads, p. 37.

[5] D. R. and Margaret Miller would eventually have nine children, adding Robert, Frederick, Charles, Marion, and Maggie by 1870. 1870 US Census.

[6] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, pp. 848-849, 1026.

[7] Ernst, Too Afraid to Cry, pp. 126-129. p. 140; Walker, Antietam Farmsteads, p. 38; Von Borcke, Memoirs, Vol. 1, pp. 226-229; Harsh, Taken at the Flood, p. 336.

[8] OR, Vol. XIX, Pt. 1, p. 218. Shortly after the battle David’s brother, Daniel, became ill and soon died of diarrhea—as did many other Sharpsburg citizens–which the family ascribed to the army’s presence.

[9] https://jacob-rohrbach-inn.com/blog/2017/03/the-farmsteads-at-antietam-david-r-miller-farm/

[10] http://antietam.stonesentinels.com/places/miller-farm/

Good job. Well researched. Enjoyed reading.

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike